How to Structure an Argumentative Essay Like a Pro

November 16, 2025

An argumentative essay is built on five core elements: a solid introduction with a clear thesis, a few body paragraphs packed with evidence, a section that tackles counterarguments, and a memorable conclusion.

Think of it like you're making a case in court. You state your position, back it up with proof, acknowledge what the other side might say, and then you deliver a closing statement that sticks with the jury.

Building Your Essay's Foundation

Before you even think about writing, you need a blueprint. An argumentative essay isn't just a long-winded opinion piece; it’s a logical framework designed to walk your reader from your initial claim to your final, persuasive point. The idea isn't just to share your view, but to build such a convincing case that your reader has to seriously consider it.

There's a reason this structure is a classic—it just works. In fact, argumentative essays are the most popular type of academic essay worldwide, making up roughly 32% of all student assignments. Why? Because this format is perfect for showing you can think critically and communicate a logical point.

The Core Components of Your Essay

Every strong argument is built on a few non-negotiable pillars. If you get these right from the start, the rest of the writing process becomes a whole lot smoother.

- The Introduction: This is your first impression. You need to grab the reader's attention with a good hook and then present your main argument in a sharp, debatable thesis statement.

- Body Paragraphs: Think of each paragraph as a mini-argument that supports your main thesis. This is where you'll use the Claim-Evidence-Warrant model to connect your points to your proof logically.

- The Counterargument: Acknowledging and shooting down opposing views is what separates a good argument from a great one. It shows you’ve thought about all sides of the issue, which instantly makes you more credible.

- The Conclusion: This is more than just a summary. You should restate your thesis with some fresh insight and leave your reader with something to think about.

To give you a clearer picture, here’s a quick breakdown of what each part does.

Quick Guide to Essay Components

| Component | Primary Function | Key Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | Grab attention and state the argument | Present a clear, debatable thesis statement |

| Body Paragraphs | Present supporting evidence and analysis | Prove the thesis with specific claims and proof |

| Counterargument | Acknowledge and refute opposing views | Strengthen your credibility by showing objectivity |

| Conclusion | Summarize and leave a final impression | Reaffirm the thesis and provide a sense of closure |

Mastering this blueprint keeps your essay from turning into a jumbled mess of ideas and helps you build a truly persuasive case.

The real power of an argumentative essay isn’t just in having a strong opinion; it’s in presenting that opinion within a logical framework that’s hard to pick apart.

Interestingly, these same principles of structure and logical flow are crucial in other areas, too. For example, they're essential when creating compelling online courses, where clear progression is vital for helping people learn effectively.

If you want to dig a bit deeper into what makes this style of writing tick, check out our guide on what argumentative writing is and how it stands apart from other formats.

Crafting a Thesis That Steers Your Argument

Think of your thesis statement as the GPS for your argumentative essay. It’s a single, sharp sentence telling your reader exactly where you’re going and why they should bother to come along. An essay without a strong thesis is like a road trip with no destination—just a random collection of stops that don't lead anywhere meaningful.

A powerful thesis is more than just a fact or a broad observation. It has to be debatable, specific, and defensible. This means someone could reasonably disagree with it, it zeroes in on a tight aspect of your topic, and you've got the evidence to back it up.

Turning a Topic into a Thesis

First things first: you need to move from a general topic to a focused, arguable claim. A classic mistake is to stop at the topic level, which almost always leads to a vague essay that's impossible to defend.

Here’s how that transformation works:

- Broad Topic: Social media's impact on teenagers. (Way too big. You could write a book on this.)

- Narrowed Focus: The effect of Instagram on teenage self-esteem. (Getting warmer, but it's still not an argument.)

- Arguable Thesis: While many believe social media connects teenagers, the curated perfection on platforms like Instagram contributes to a significant decline in adolescent self-esteem by creating unrealistic social comparison standards.

This final version works. It takes a clear stance, hints at the main points (unrealistic standards), and gives the reader a roadmap for the rest of the essay.

The Litmus Test for a Strong Thesis

Before you get too attached to your thesis, run it through this quick quality check. A solid thesis needs to pass all three tests. If it fails even one, it's time to head back to the drawing board.

- Is it arguable? Your thesis must put a position on the table that people could challenge. A statement like, "Pollution is bad for the environment," is a fact, not an argument. A much better thesis would be, "Implementing a federal carbon tax is the most effective strategy for significantly reducing industrial pollution." See the difference?

- Is it specific? Ditch vague words like "good," "bad," "successful," or "interesting." Your thesis needs to state why something is good or how a program is successful. Instead of, "City-wide recycling programs are beneficial," try this: "Implementing a mandatory city-wide recycling program significantly reduces landfill waste and generates municipal revenue through the sale of recycled materials."

- Is it a roadmap? A great thesis should subtly outline the structure of your argument. The best ones often hint at the main points you'll cover in your body paragraphs, giving your reader a clear preview of your essay’s logic.

A great thesis isn't just a claim; it’s a promise to your reader. It promises a logical, well-supported argument that will explore a specific aspect of a topic in a meaningful way.

Learning this skill pays off far beyond the classroom. The ability to form a concise, persuasive argument is essential everywhere. For instance, you use the exact same principles when you craft a compelling personal statement for college or a job, where you're basically arguing for your own qualifications.

If you’re stuck, check out a variety of strong thesis statement examples. Seeing how different claims are structured across various subjects can spark ideas and help you get a feel for what works. It's one of the best ways to sharpen your own approach and create a thesis that truly drives your essay forward.

Building Body Paragraphs That Persuade

If your thesis is the essay's North Star, your body paragraphs are the individual steps you take to get there. Each one needs to be a self-contained, persuasive unit that pushes your whole argument forward. It’s not enough to just list facts; you have to build paragraphs that powerfully connect your evidence back to your main point.

The secret? A simple but powerful framework known as the Claim, Evidence, Warrant (CEW) model. Think of it as the DNA of a convincing body paragraph. Getting this structure down is what separates a summary from a real argument.

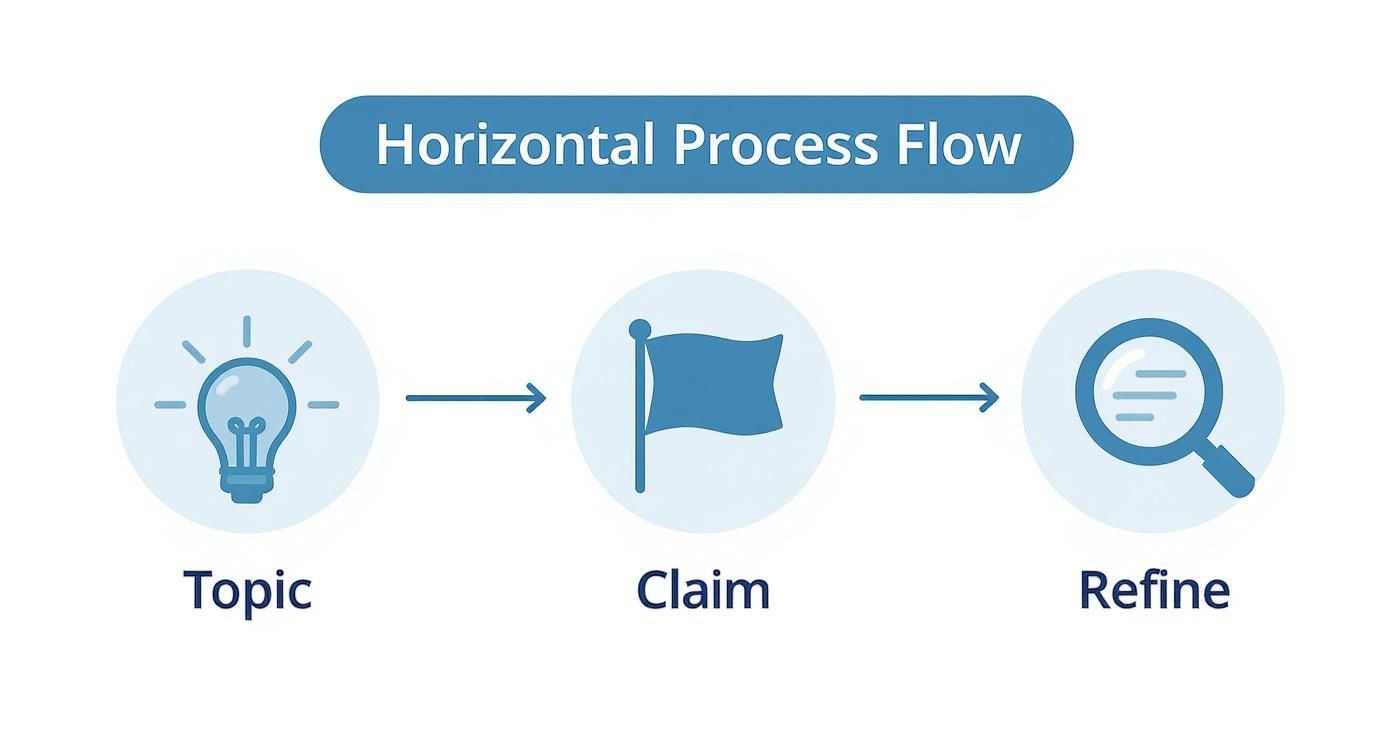

This visual gives you a sense of the flow, moving from a big topic to a sharp, arguable claim—the jumping-off point for every body paragraph.

As you can see, a strong claim acts as the foundation. It guides what evidence you choose and the logic you use to analyze it.

The Claim: Your Topic Sentence

Every great body paragraph kicks off with a strong claim. This is basically a mini-thesis for that specific section, and it lives in your topic sentence. It has to do two things: directly support your main thesis and introduce the single idea the paragraph is about to prove.

A common mistake is writing a topic sentence that's just a fact. For example, "Many companies now offer remote work options." True, but where's the argument?

A much stronger claim would be: "Companies that embrace remote work options gain a significant competitive advantage by accessing a broader, more diverse talent pool." See the difference? This one is debatable and immediately tells the reader what you intend to prove.

For more on nailing this first sentence, our article offers some great insights into crafting effective topic sentences for body paragraphs.

The Evidence: Your Proof

Once you've made your claim, you have to back it up with evidence. This is the "what" of your paragraph—the concrete proof that supports what you just said. Good evidence comes in many forms, and mixing it up usually makes for a more solid argument.

Here’s what effective evidence looks like:

- Statistics and Data: Numbers give your point weight and make it feel concrete.

- Expert Testimony: Quoting or paraphrasing an authority in the field lends your claim instant credibility.

- Case Studies or Anecdotes: A specific, real-world example can make your point more relatable and easier to grasp.

- Historical Facts: These can provide important context or reveal a pattern over time.

The most persuasive essays often use 2-3 distinct pieces of evidence in a single paragraph, blending data with expert opinions and tangible examples to build a convincing case.

The Warrant: Your Connection

This is the most critical—and most often forgotten—part of the CEW model. The warrant is the "so what?" of your paragraph. It’s your explanation of how and why the evidence you just presented actually proves your claim.

Never, ever assume your reader will connect the dots on their own. That's your job. The warrant is where you analyze, interpret, and explain the significance of your proof.

The warrant is the intellectual glue of your paragraph. Without it, your evidence is just a disconnected list of facts. With it, you transform information into a persuasive argument.

Let’s see how it all works together.

- Claim: The city’s new bike lane initiative has significantly improved urban mobility and reduced traffic congestion for commuters.

- Evidence: According to a report from the Municipal Transportation Agency, morning commute times in the downtown corridor have decreased by an average of 15% since the lanes were installed six months ago. Additionally, the report noted a 25% increase in bicycle traffic during peak hours.

- Warrant: This decrease in commute times, coupled with the surge in cyclists, demonstrates that the bike lanes are not just an alternative but a viable solution that is actively pulling cars off the road. By providing a safe and efficient route, the city has successfully incentivized a shift in transportation habits, directly leading to less congested streets and a more fluid traffic flow for everyone.

Handling Counterarguments with Confidence

Taking the time to engage with the other side of the argument is probably the single most powerful thing you can do to elevate an essay. It’s what separates a good paper from a great one.

It shows you’ve done more than just hunt for evidence that supports your own ideas. You’ve wrestled with the tough parts of the issue, and your position still comes out on top. This isn’t a sign of weakness—it’s a mark of genuine intellectual confidence.

A lot of students skip this part. They worry it will make their own claims look shaky. But the opposite is true. When you can state an opposing view fairly and then take it apart, your own credibility skyrockets. You're essentially telling your reader, "Look, I've considered all the angles, and this is still the most logical conclusion."

Find the Counterarguments That Actually Matter

Not all opposing views are worth your time. The first step is to zero in on the most significant, logical challenges to your thesis. Forget about "straw man" arguments that are easy to push over. You’re looking for the tough questions—the points a smart opponent would actually raise.

To find them, ask yourself a few things:

- What's the strongest point against me? If you had to argue the other side, what would you lead with?

- Where are the weak spots in my own evidence? Could a skeptical reader find a loophole in your data or a flaw in your examples?

- What do the experts disagree on? A quick search usually reveals the core debates in any field. This is where the good stuff is.

Focusing on these legitimate counterclaims shows you're engaging with the topic on a much deeper level.

Present Opposing Views Fairly

Once you’ve got a solid counterargument, your job is to present it accurately and charitably. Don't just brush it off with something like, "Some people wrongly believe..." That just makes you sound biased.

Instead, state the opposing view clearly and respectfully. Use neutral language. A good rule of thumb is to summarize it in a way that someone who holds that belief would agree with.

Let's say you're arguing for stricter gun control. A fair take on a counterargument might look like this:

Proponents of looser gun regulations often argue that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual's right to bear arms for self-defense. They suggest that more laws would infringe upon this constitutional freedom while failing to deter criminals, who will always find ways to obtain firearms illegally.

This phrasing shows you understand the logic behind the opposition. That sets you up perfectly to explain why your position is still more compelling.

Refute with Logic and Evidence

Now it’s time to pivot back and dismantle that counterargument. This is where you bring your own reasoning and evidence into play. There are a couple of smart ways to do this.

1. The Direct Rebuttal

This is the most straightforward approach. You challenge the counterargument head-on with stronger, more convincing proof.

- Example: "While the Second Amendment does protect this right, historical and legal precedent shows it is not absolute. This right has always been subject to reasonable regulation for public safety, a principle upheld in numerous court cases."

2. The Concession

Here's a move that feels counterintuitive but is surprisingly powerful. You can actually agree with a small part of the opposing argument—this is called making a concession—before explaining why your overall position is still better.

- Example: "It's understandable to be concerned about personal safety, and it's true that some criminals will always find ways around the law. However, comprehensive data from countries with stricter regulations shows a clear correlation between tighter gun laws and a significant reduction in firearm-related homicides, proving such measures are effective on a broad scale."

This technique shows you’re a balanced, reasonable thinker. It makes your final conclusion feel earned and much harder to challenge.

Creating a Seamless Flow Between Your Ideas

Even the most brilliant, evidence-packed paragraphs will fall flat if they feel like isolated islands of thought. A truly great essay guides the reader on a smooth, logical journey from one point to the next.

This isn’t just about sprinkling in a few "howevers" and "therefores." It’s about building conceptual bridges between your ideas so your reader can follow along without getting lost. Your job is to make their job easy.

When you nail the flow, you turn a collection of strong claims into a single, cohesive argument that’s much harder to poke holes in.

Beyond Basic Transition Words

Think of flow on two levels: between paragraphs and within them.

Inside a paragraph, transitions help you connect a piece of evidence back to your analysis. Between paragraphs, they create that logical path that makes the whole essay feel intentional and connected.

The best transitions often happen right at the end of a paragraph. You can subtly hint at the idea you’re about to explore next, creating a natural hand-off.

For instance, you might end a paragraph about the economic costs of a new policy by saying, "While the financial burden is clear, the social consequences present an even more compelling reason for reevaluation." Boom. That sentence perfectly tees up your next paragraph on social impacts.

An essay with strong flow reads like a story where each scene logically follows the last. An essay without it feels like a collection of disconnected short stories, leaving the reader to figure out how they all relate.

Choosing the Right Phrase for the Job

The specific transitional phrase you choose signals the relationship between your ideas. Picking the wrong one can completely derail your reader and weaken your point.

Are you adding a similar point? Showing a contrast? Revealing a cause-and-effect link? Each function has its own set of tools.

A good transition makes the connection between your ideas explicit. It tells the reader exactly how Point A relates to Point B, so they never have to guess.

Here’s a quick guide to help you pick the perfect phrase to articulate those logical connections in your writing.

Transitional Phrases for Logical Flow

| Purpose | Example Phrases | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| To Add Information | Additionally, Furthermore, In addition, Moreover | When you're presenting another piece of evidence or a point that reinforces the previous one. |

| To Show Contrast | However, On the other hand, Conversely, Nevertheless | When you're introducing a conflicting idea, a counterargument, or an opposing piece of evidence. |

| To Provide an Example | For example, For instance, To illustrate, Specifically | When you want to clarify a general statement with a concrete example or a case study. |

| To Show Cause & Effect | Consequently, As a result, Therefore, Thus | When you're explaining the outcome or result of a preceding action or idea. |

| To Emphasize a Point | Clearly, Indeed, In fact, Most importantly | When you want to signal to the reader that a particular idea is especially significant to your argument. |

By mastering these connections, you do more than just improve your writing style. You take control of the reader's experience, guiding them step-by-step through your reasoning until your conclusion feels not just possible, but inevitable.

That command of flow is a true hallmark of sophisticated, persuasive writing.

Bringing It All Home: Your Conclusion and Final Polish

Your conclusion is your last chance to make your argument stick. Don’t treat it like an afterthought. So many students just rehash what they've already said, but a great conclusion does more than just summarize—it synthesizes your points and drives home why any of this even matters.

Think of it as your closing argument. You’ve laid out all the evidence. Now you need to connect the dots for the jury one last time and leave them with a powerful thought that seals the deal.

How to Write a Conclusion That Clicks

A strong conclusion should wrap things up neatly without bringing in any new evidence. The real goal is to give the reader a sense of closure while reminding them of just how solid your argument is.

First, circle back to your thesis, but say it differently. You’re not just copying and pasting from your intro. You’ve spent the whole essay proving your point, so restate it with more confidence and authority.

Next, briefly weave your main points together. Don't just list them out again. Show the reader how each piece of evidence you presented connects to create one, cohesive argument. You’re reminding them of the logical journey they just took.

The best conclusions always answer the "so what?" question. They tell the reader why your argument is important in the bigger picture and what the implications are.

Finally, leave them with something to think about. This could be a call to action, a provocative question, or a glimpse into the future of the issue. That final sentence is what will echo in their mind long after they've finished reading.

Time to Polish: The Revision Checklist

Once you've got a full draft, the real work begins. You have to switch hats from writer to editor, and that means getting critical. It's time to comb through your work, looking at both the big picture and the nitty-gritty details.

Here’s a checklist to guide you through the polishing phase:

- Does It All Connect? Read through your argument one more time. Is the flow logical? Make sure your claims, evidence, and warrants all chain together seamlessly to support your thesis.

- Clear and to the Point? Hunt down any jargon or wordy phrases. If you can say something in five words instead of ten, do it. Every sentence should be crisp and purposeful.

- Proofread Like a Pro: This is a big one. Read your essay out loud. It’s the best way to catch awkward sentences and typos your eyes might skim over. Meticulously check for any grammar, spelling, or punctuation errors.

- Citations and Formatting on Point? Double-check that every source is cited perfectly in whatever style you’re using (like MLA or APA). Make sure your margins, font, and spacing are exactly what the instructions call for.

Common Questions About Essay Structure

We've all been there. You have your argument mapped out, but then you get stuck on the nitty-gritty details of structure. Let's walk through some of the questions I hear most often from students, so you can stop second-guessing and start writing.

How Many Paragraphs Should My Essay Be?

Everyone wants a magic number, but there isn't one. The classic five-paragraph model—an intro, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion—is a great training ground. It teaches you the basics.

But a truly complex argument can't be squeezed into just three points. The real answer is your essay should have as many paragraphs as you have distinct claims to prove. The argument dictates the length, not the other way around.

Interestingly, how we structure essays can even be a cultural thing. A cross-cultural analysis found that Italian learners tend to write essays with around 6.94 paragraphs, while Tswana speakers average 5.98. It’s a cool reminder that there are many ways to build a coherent argument. You can dive deeper into these structural differences in student writing if you're curious.

Focus on fully developing each point instead of hitting an arbitrary paragraph count. Your essay is done when your thesis is convincingly proven.

Can My Thesis Statement Be More Than One Sentence?

The gold standard is a single, sharp sentence. But can it be two? Yes, but it’s rare. You should only stretch your thesis to two sentences if you absolutely cannot distill your argument and its nuances into one.

When in doubt, stick to one sentence. It forces you to get crystal clear on your position, which is exactly what a strong thesis is supposed to do.

Where Does the Counterargument Go?

You’ve got a few smart options here, and the best one depends on the flow of your argument.

- Right after the introduction: Get it out of the way early. This shows your reader you’ve considered other perspectives right from the start.

- Just before the conclusion: This is a powerful spot. You can use it to dismantle any final doubts the reader might have before you wrap things up.

- Inside a body paragraph: If a counterargument is directly related to one of your claims, tackle it right then and there. Introduce your point, then immediately pivot to refute the opposing view.

Think about which placement will make your argument feel the most logical and persuasive. There's no single right answer, only the one that works best for your essay.

Feeling like your AI-drafted essays sound a bit... robotic? Natural Write can fix that in one click. It instantly humanizes your text, making sure it flows naturally and reads like you wrote it yourself. Polish your next essay and bypass AI detectors at https://naturalwrite.com.