How to Create an Annotated Bibliography: A Quick Guide to Stronger Research

January 5, 2026

Before you can write an annotated bibliography, you need to find and evaluate credible sources. For each one, you’ll write a concise paragraph that summarizes, assesses, and reflects on its relevance to your research. This simple process turns a basic reference list into a serious critical thinking tool.

What Is an Annotated Bibliography Really For

Let’s get beyond the textbook definition. An annotated bibliography is way more than just another assignment to check off a list; it's a foundational step for any serious research project. It forces you to actually engage with your sources instead of just passively collecting them.

Picture a grad student prepping for their thesis. By building this document, they're essentially creating a map of all the existing research. They can spot the key arguments, find gaps in the conversation, and sharpen their own thesis statement before ever writing a single chapter. The process itself builds a stronger, more informed argument from the ground up.

A Tool for Critical Engagement

An annotated bibliography really has two jobs, both of which are crucial for academic success. It’s a summary and an evaluation, all rolled into one. This structure pushes you to think critically about every single piece of information you gather.

You aren't just saying what a source argues. You're also asking:

- How credible is the author? Is this a peer-reviewed study from a top journal, or is it a biased opinion piece from a random blog?

- Is the information still relevant? A tech article from 20 years ago might be totally obsolete, but a foundational philosophy text is probably still essential.

- How does this source fit into my project? Does it support your main point? Offer a compelling counterargument? Or just provide some much-needed background context?

As you can see, the real value comes from moving past a simple summary and into a thoughtful evaluation of what each source actually brings to the table.

Sharpening Your Research Skills

This rigorous process has a real, measurable impact. A multi-year study found that after students took workshops on creating annotated bibliographies, their use of high-quality scientific literature jumped to 51%. At the same time, their reliance on unreliable web pages dropped from 17% to just 8%.

This skill is so vital that it’s a staple in 80% of U.S. undergraduate research courses. If you're curious, you can read the full research about these academic improvements to see just how big of a difference it makes.

By forcing you to spell out a source's value and limitations, an annotated bibliography helps you truly own your research. It prevents unintentional plagiarism and builds a rock-solid foundation for whatever you're writing.

Finding and Evaluating Sources That Count

The strength of your annotated bibliography hinges entirely on the quality of your sources. And while a quick Google search is a tempting place to start, serious academic work means digging deeper. You have to move past the first page of search results and into the world of scholarly databases.

Your university library is your best friend here. It’s a gateway to powerful databases like JSTOR, ProQuest, and Google Scholar—all for free. These platforms are packed with peer-reviewed journal articles, academic books, and primary source documents. This is the stuff that adds real weight and credibility to your research.

A Framework for Evaluating Sources

Okay, so you’ve gathered a list of potential sources. Now comes the real challenge: figuring out which ones are actually worth your time.

Not all published material is created equal. A popular blog post, for instance, just doesn't have the same rigorous vetting as a peer-reviewed journal article. To separate the good from the questionable, many researchers I know swear by the CRAAP test. It's a simple, memorable framework for vetting any source you come across.

Here’s what to look for:

- Currency: When was it published? A 20-year-old article on computer science is probably ancient history, but a historical analysis from the same era might still be foundational.

- Relevance: How closely does it actually relate to your research question? A source can be perfectly credible but totally irrelevant to your specific topic.

- Authority: Who wrote it? Look up their credentials and where they work. An expert in the field obviously carries more weight than an anonymous writer.

- Accuracy: Can the information be verified? Check for citations, references, and evidence-based claims. Peer-reviewed articles have already been checked for accuracy by other experts, which is a huge plus.

- Purpose: Why does this source exist? Is it meant to inform, persuade, or sell you something? Understanding the author’s intent helps you spot potential bias from a mile away.

Running every source through this checklist ensures you’re building your bibliography on a foundation of solid, trustworthy information. These evaluation skills are essential for all academic work; it’s why learning how to write a literature review for a dissertation often starts with this exact same process.

Staying Organized and Avoiding Overwhelm

Research can get chaotic. Fast. With dozens of articles, books, and websites piling up, it’s ridiculously easy to lose track of what you’ve found and why it even matters. This is where research management tools become absolute lifesavers.

Think of a tool like Zotero or Mendeley as your personal research assistant. They don't just store your sources; they help you organize your thoughts, generate citations, and keep your project on track from start to finish.

These tools let you save sources directly from your browser, tack on notes, and create folders for different subtopics. When it’s finally time to write your annotated bibliography, everything is already organized in one place. Trust me, it saves an incredible amount of time and stress.

Of course, finding and organizing sources is only half the battle. You also have to use them correctly and maintain academic integrity. Knowing how to check for plagiarism in Google Docs is just as important as finding good articles. A well-organized workflow helps you stay on top of it all.

Choosing the Right Annotation Style

Once you’ve gathered your sources, the next big decision is how you're going to write about them. An annotation isn't a one-size-fits-all task; the style you choose has to line up with what your assignment is actually asking for. Getting this right from the start is the key to building an annotated bibliography that actually does its job.

The style you pick determines how deep you need to go. Are you just supposed to report what a source says, or are you expected to dig in and challenge its arguments? Figuring this out early will save you a ton of rewriting later. Most of the time, you'll be asked to use one of three main approaches.

The Descriptive or Summary Annotation

Think of this as the most straightforward style. Your main job is simply to summarize a source's central argument without throwing in your own two cents. It’s a neutral, objective report on what the author wrote.

This style works perfectly when the goal is just to create an inventory of the research out there. For instance, if you're pulling together a reading list for a group project, a quick descriptive annotation tells everyone what each article is about at a glance.

- What it does: It answers the question, "What is this source about?"

- What it avoids: It completely steers clear of personal opinions, critiques, or reflections on whether the source is any good.

You're basically acting like a reporter, just conveying the facts: the author's main points, their evidence, and how it all wraps up.

The Analytical or Critical Annotation

This is where you really get to flex your critical thinking muscles. An analytical or critical annotation goes way beyond a simple summary. After you briefly cover the source's main ideas, your job is to evaluate its strengths, weaknesses, and overall credibility.

For example, if you were analyzing a scientific study, you wouldn't just state the results. You'd also look at the methodology. Was the sample size big enough? Do the authors' conclusions actually hold up based on their data? You might even compare its findings to other studies in the field to see how it fits into the broader conversation.

A critical annotation isn't about being negative; it's about being evaluative. Your goal is to provide a sharp, informed judgment on the source's quality, reliability, and contribution to the topic.

This style demands a much deeper read. You have to actively question the author’s arguments, look for potential bias, and decide for yourself how valuable the source truly is.

Before we get to the third type, here's a quick table to help you keep these styles straight. It's a handy reference for remembering what each one is for.

Comparing Annotation Types

| Annotation Type | Main Purpose | Key Questions to Answer |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptive/Summary | To inform the reader about the source's content. | What is the main argument? What topics are covered? What are the key findings? |

| Analytical/Critical | To evaluate the source's quality and reliability. | Is the argument convincing? What are the strengths and weaknesses? Is the evidence reliable? How does it compare to other sources? |

| Combination | To summarize, evaluate, and connect the source to your own work. | All of the above, plus: How is this source useful for my research? How will I use it in my project? |

This little chart makes it easy to see the focus of each style at a glance.

The Combination Annotation

Just like the name says, this style blends the descriptive and analytical approaches. It’s probably the most common type you'll see in academic assignments because it gives the fullest picture of a source. It proves you not only understand the material but can also think critically about its value.

A solid combination annotation usually does three things:

- Summarize: First, you briefly state the source's main argument and key points.

- Analyze: Next, you evaluate its strengths, weaknesses, and any potential biases you've spotted.

- Reflect: Finally, you explain exactly how this source is relevant to your own research project.

So, after summarizing an opinion piece, you might analyze how the author uses emotional language versus hard data, and then reflect on how their perspective either supports or challenges your own thesis. This all-in-one approach really showcases your ability to create an annotated bibliography that's both informative and insightful.

How to Craft Powerful and Insightful Annotations

Alright, this is where your critical thinking really gets to shine. Writing a sharp annotation is what turns a simple list of sources into a compelling piece of analysis. It’s the moment you stop just listing research and start building an argument.

Think of a great annotation—usually around 150 words—as your opportunity to prove you’ve wrestled with the material. It’s more than a summary; it’s a snapshot of your engagement.

It all starts with active reading. Don't just skim for quotes. Read with a pencil in hand, highlighting the author's main thesis, the evidence they lean on, and anything that makes you pause, whether it's a brilliant insight or a questionable claim. Do this groundwork, and the writing part becomes so much easier.

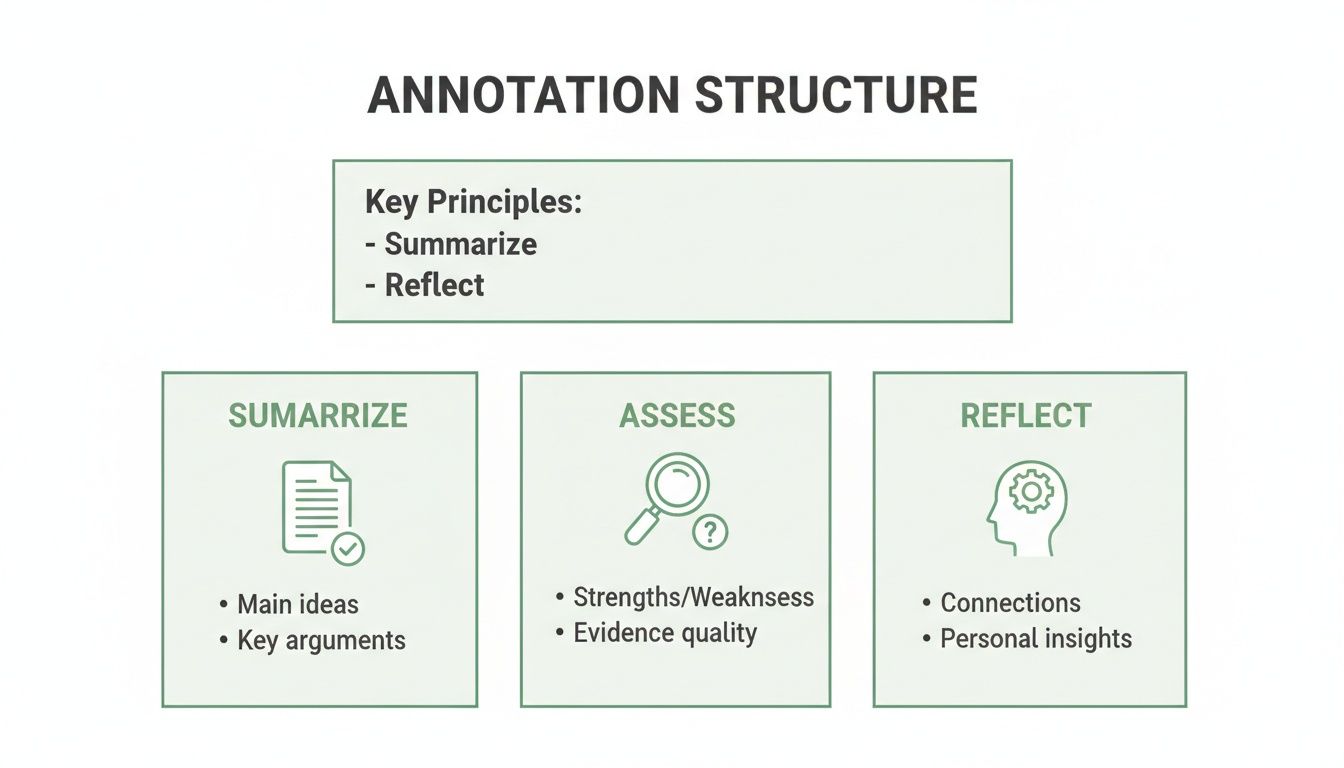

The Three Pillars of a Great Annotation

Every truly effective annotation does three things: it summarizes, it assesses, and it reflects. If you can master this simple sequence, you'll know how to create an annotated bibliography that's not just informative but genuinely insightful.

- Summarize: First, boil down the source's main point into your own words.

- Assess: Next, evaluate its strengths and weaknesses. Question its credibility, bias, or the methods it uses.

- Reflect: Finally, explain why it matters to your project. Does it support your thesis? Offer a counterargument? Provide crucial background info?

Learning to do this well is a game-changer. Research actually shows that students who write annotations read their sources 40% more critically than those who just collect citations. This leads to stronger arguments in 85% of cases. You also get to grips with an author's point of view in 70% more depth. You can discover more insights about these research findings to see the full impact.

Of course, the first step—summarizing—is a skill in itself. Mastering a few effective summary writing techniques will make your annotations clearer and more concise from the get-go.

From Summary to Analysis with Sentence Starters

Making the leap from a simple summary to a real analysis can feel tricky. Sometimes, all you need is a little nudge to get your analytical gears turning. That's where sentence starters come in.

Think of these as springboards for your critical thoughts:

- To Highlight Strengths: "The author convincingly argues..." or "A key strength of this study is..."

- To Point Out Weaknesses: "However, the argument is less persuasive when..." or "A limitation of this source is its reliance on..."

- To Connect to Your Work: "This source is particularly useful for my project because it provides..." or "This perspective challenges my initial thesis by..."

These aren't just fill-in-the-blanks. They're scaffolds that help you structure your thoughts into a coherent paragraph that goes way beyond a high-school book report.

Your unique voice is the most valuable part of an annotation. While AI tools can help generate a first draft or summarize dense text, the critical assessment and reflection must be yours alone. Use them as a starting point, but always refine and rewrite to ensure your personal analysis shines through. This maintains academic integrity and produces a far more compelling bibliography.

Formatting Your Bibliography in APA, MLA, and Chicago

Getting the formatting right is more than just busywork—it's about showing you respect the academic conversation you're joining. Each citation style has its own quirks, and mastering them shows your reader you've paid attention to the details.

Let's break down the big three: APA, MLA, and Chicago. Think of this as your field guide for building a bibliography that looks clean, professional, and correct. We'll cover everything from hanging indents to title capitalization, with clear examples to help you sidestep those common formatting traps.

Before we dive into the specific styles, here's a great visual that breaks down what a strong annotation actually includes.

It really comes down to those three steps: summarize, assess, and reflect. Keep that in mind as you write each entry.

APA 7th Edition Formatting

You’ll run into APA (American Psychological Association) style all the time in the social sciences. The rules are pretty straightforward: alphabetize entries by the author's last name, double-space everything, and use a 0.5-inch hanging indent for every line after the first.

Here’s what that looks like in action for a journal article:

Jones, A. B. (2020). The impact of digital media on adolescent development. Journal of Youth Studies, 23(4), 451–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1594191

In this study, Jones explores how increased screen time affects cognitive and social skills in teenagers. The author uses a longitudinal study of 500 adolescents to argue that while digital media can enhance certain problem-solving abilities, it often correlates with diminished face-to-face communication skills. This research is highly relevant as it provides recent, data-driven evidence supporting my thesis on technology's role in modern education. The methodology is robust, though the sample is limited to a single urban area, which could affect its generalizability.

MLA 9th Edition Formatting

If you’re in the humanities, MLA (Modern Language Association) is your go-to. It’s a lot like APA in its core structure—double spacing and a 0.5-inch hanging indent are required here, too. The main difference you'll spot is how it handles titles; MLA uses title case for both article and book titles.

Let's see an example for a book:

Smith, Jane. The Digital Labyrinth: Navigating Information in the New Age. University Press, 2021.

Smith's book provides a comprehensive overview of information literacy in the digital era. She argues that the ability to critically evaluate online sources is the most crucial skill for modern students. The author breaks down complex concepts like algorithmic bias and misinformation, offering practical strategies for identifying credible sources. This work is essential for my research as it provides a theoretical framework for the importance of media literacy. I will use her chapter on "fake news" to support my argument that schools need to update their curricula.

Chicago 17th Edition Notes and Bibliography

Chicago style can feel a bit more complex because it offers two systems. For an annotated bibliography, you’ll almost always use the Notes and Bibliography system. It sticks to the familiar hanging indent and double-spacing format. The real distinctions are in the finer details, like how it treats author names and publication information.

If this is your first time wrestling with Chicago, our guide on how to cite sources in a research paper offers a great primer on the fundamentals.

Here’s a Chicago-style example:

Williams, Samuel. “Rethinking Urban Spaces for Community Engagement.” Journal of Urban Planning 45, no. 3 (2019): 210–225. https://doi.org/10.1086/123456.

Williams examines three case studies of urban renewal projects to assess their impact on community cohesion. His central argument is that successful projects prioritize public gathering spaces and pedestrian-friendly designs over commercial development. The article’s strength lies in its mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative survey data with qualitative interviews. This source directly supports my research by offering concrete examples of effective urban planning, which I can contrast with less successful local initiatives.

Common Questions About Annotated Bibliographies

Even with a solid plan, a few questions always seem to pop up when you're putting together an annotated bibliography. It's totally normal. Getting those nagging questions answered clears up the confusion and lets you move forward with confidence.

Let's tackle a few of the most common ones I hear from students.

What’s the Difference Between an Annotated Bibliography and a Literature Review?

This is a big one, and it's easy to get them mixed up.

Think of an annotated bibliography as a list of potential ingredients. It’s an organized collection of your sources, where each entry gets its own standalone paragraph—the annotation—that explains what it is and why it's useful. You're evaluating each source on its own merit.

A literature review, on the other hand, is the finished meal. It’s a cohesive essay that weaves together the arguments from many sources to tell a bigger story. It synthesizes what others have said, identifies trends, and points out gaps in the existing research. The bibliography is the prep work; the review is the narrative you build from it.

How Long Should Each Annotation Be?

Your instructor's guidelines are always the final word, but a good rule of thumb is to aim for around 150 words. That’s usually one solid paragraph per source.

This gives you just enough space to be thorough without rambling. Your goal is to summarize the author's main point, offer a quick critique of its strengths or weaknesses, and explain exactly how it fits into your project. It’s a great exercise in being both analytical and concise.

The most common mistake is writing a summary and stopping there. A true annotation needs your critical voice. You have to assess the source’s value and reflect on its specific use in your research for it to be complete.

Can I Use AI to Help Write My Annotations?

Yes, but you have to be smart about it. AI writers can be a great starting point, especially for getting a quick summary of a dense academic article or helping you organize your initial thoughts.

However—and this is critical—you must never submit AI-generated text as your own. The most important parts of an annotation are the critical evaluation and your personal reflection on how you'll use the source. That requires your brain. Misusing AI can land you in hot water with your school's academic integrity policies.

You can learn more about how to avoid plagiarism to make sure you're using these tools the right way. Always, always rewrite the AI's output and infuse it with your own perspective.

Ready to refine your AI-generated drafts into polished, human-like text? Natural Write can help you transform robotic writing into clear and natural prose that bypasses AI detectors. Check out the free tool at https://naturalwrite.com and humanize your content with one click.