how to write a literature review for dissertation: a guide

December 2, 2025

A literature review is more than just a summary of what others have said. It’s a critical piece of scholarship where you map the existing research landscape to show exactly where your own work fits in, what gaps it fills, and why it matters.

This process involves a few key stages: defining your scope, systematically hunting down sources, weaving their findings together, and finally, drafting a compelling argument that situates your dissertation in the ongoing scholarly conversation.

Defining the Scope of Your Literature Review

Before you even think about diving into academic databases, you need to set some clear boundaries. This is the strategic part. A well-defined scope is your best defence against the information overload that can easily derail a dissertation.

Think of it this way: your dissertation is making an argument. The literature review is the evidence you're presenting to prove why that argument is necessary. Without clear parameters, you'll end up with a mountain of irrelevant evidence that just weakens your case. Defining your scope early on turns a vague idea into a focused, manageable project.

Starting With Your Research Question

Your research question is the anchor for everything. It’s the compass that tells you what’s relevant and what’s just noise. To get this right, you first need to craft a powerful open-ended research question that genuinely drives your investigation. A strong question is what helps you decide what to include—and, just as importantly, what to exclude.

These criteria might include things like:

- Time Period: Are you focusing only on research from the last 10 years, or do you need to trace a concept’s history?

- Geography: Is your study limited to a specific country, region, or cultural context?

- Methodology: Are you only interested in quantitative studies, or are you bringing in qualitative or mixed-methods research, too?

- Theoretical Frameworks: Are there specific theories you plan to engage with, build on, or even challenge?

Sorting this out upfront will save you countless hours. It’s the difference between fishing in the entire ocean versus casting your net in a well-stocked lake where you know what you’re looking for.

Building a Preliminary Outline

Once your boundaries are in place, a preliminary outline becomes your roadmap. This isn't some rigid document you have to stick to. Think of it as a flexible blueprint that will grow and change as you read. It’s there to help you organize your thoughts and start seeing the connections between different studies.

Our post on how to write a research paper outline has a great framework you can adapt for this.

A huge mistake I see all the time is treating the literature review like a series of book reports, just summarizing one study after another. That’s not the goal. Your job is to map the scholarly conversation—to identify the key debates, the points of agreement, and, most importantly, the unanswered questions.

Your outline should be thematic. Organize it around the core concepts and arguments in your field, not just by author or publication date. This helps you group sources by the ideas they’re wrestling with. As you start filling it in, you'll see a story begin to emerge. It’s a story that should lead, logically and inevitably, to the gap your dissertation is about to fill.

Finding and Evaluating Your Sources

A killer literature review is built on a foundation of high-quality, relevant sources. This is where you move past basic keyword searches and into a strategic process of hunting down and evaluating the right material. The goal is to stop feeling overwhelmed by a scattered, endless search and start a methodical process that uncovers the best evidence for your research.

This means getting comfortable with advanced search techniques in academic databases to pinpoint exactly what you need. It also involves meticulously documenting your search process (a must for academic rigour) and, most importantly, learning how to critically size up every single source you find.

Mastering Strategic Search Techniques

Just typing a few keywords into a single database won’t cut it at the dissertation level. To do this right, you have to think like a seasoned researcher and use the powerful tools baked into major academic databases.

Platforms like Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed have advanced search operators that let you refine your queries with incredible precision. Don't just search for "climate change adaptation." Instead, use operators to build a much smarter query.

Here’s a look at the kind of interface you’ll see in a database like Scopus.

This lets you combine keywords, authors, and other fields to zero in on the most relevant literature.

For example, a search string might look like this: ("climate change" OR "global warming") AND ("urban adaptation" OR "city resilience") AND ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "policy" ) ) AND PUBYEAR > 2019. This query is looking for recent articles that specifically mention "policy" in their title, abstract, or keywords, making sure you find literature directly tied to governance and strategy.

Developing a Systematic Evaluation Process

Once you start pulling articles, the real work begins: evaluation. Not all sources are created equal, and your ability to distinguish a landmark study from a weak one is a critical academic skill. You’re curating a collection, not just making a long list of everything ever published.

A comprehensive analysis of dissertation literature reviews found a direct link between effectiveness and this systematic approach. The research showed that over 70% of successful dissertations included at least 80% peer-reviewed journal articles, and 92% prioritized publications from the last five years. You can dig into those findings here to see how they apply to your own work.

The single most important question to ask yourself is: "How does this paper move the conversation forward?" A good source doesn't just parrot old ideas; it engages with them, challenges them, or applies them in a new way.

With dozens of papers on your plate, you need a system to keep track of everything. It's a good idea to master a robust note-taking template to keep your research organized and instantly accessible. Trust me, this will save you from losing track of brilliant insights as your source list grows.

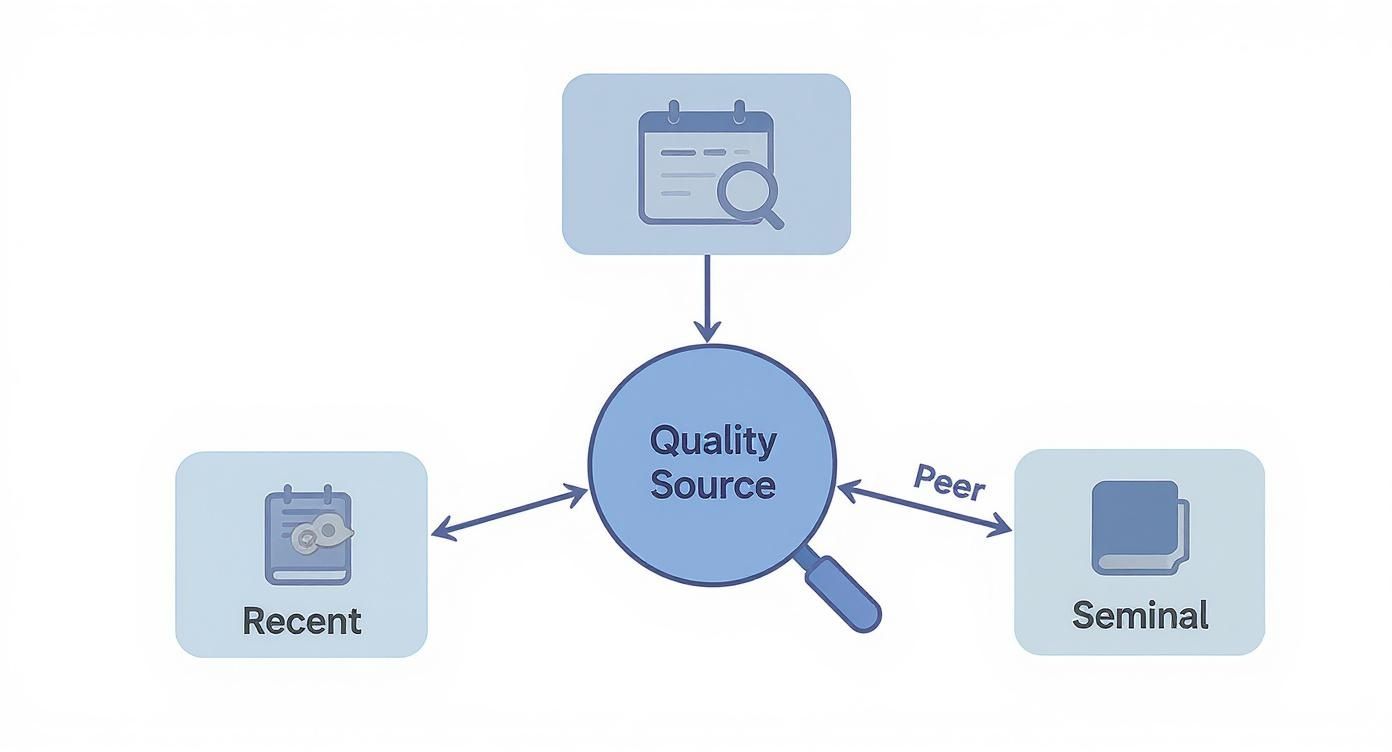

Balancing Seminal Works with Recent Research

While fresh, peer-reviewed articles are the backbone of your review, don't forget about the foundational, or seminal, works in your field. These are the classics—the theoretical papers and groundbreaking studies that everyone cites. They started the entire conversation.

So, how do you find them? Pay attention to which sources are cited over and over again in the recent articles you’re reading. If you see the same 2005 paper pop up in a dozen different studies from 2023, that’s a huge flashing sign that it’s a seminal work you absolutely need to read.

Here’s a quick framework for evaluating any source that crosses your desk:

- Relevance: Does this source directly address your research question or a key theme in your outline? Be ruthless. If it’s only sort of related, set it aside for now.

- Authority: Who wrote it? Are they established experts? Is the journal reputable and peer-reviewed? Check its standing in the field.

- Methodology: For empirical studies, is the research design sound? Are the methods actually appropriate for the questions being asked? A flawed methodology can completely invalidate a study’s conclusions.

- Contribution: What new knowledge or perspective does this source bring to the table? Does it identify a new problem, propose a different theory, or present truly novel findings?

This critical appraisal process is what separates a dissertation-level literature review from a simple book report. Your job isn’t just to report what others have said. It’s to evaluate their arguments and evidence to build a compelling case of your own.

Synthesizing Sources into a Coherent Argument

This is where the magic happens. It’s the moment you stop being a summarizer of papers and become a scholar building an argument.

Anyone can list what others have found, one after another. That creates a disconnected laundry list, not a literature review. Your goal is to weave individual studies into a single, compelling narrative that tells the story of your research field.

Synthesis is all about making connections. Think of it as mapping out the conversations happening between the papers you’ve read. Who agrees with whom? Where are the major points of conflict? How have the big ideas shifted over time? Your job is to guide the reader through this intellectual landscape, leading them logically to the exact gap your dissertation is designed to fill.

Choosing Your Organizational Structure

Before you start writing, you need a blueprint. How you structure your literature review will make or break its narrative flow and persuasive power. There’s no single "best" way—the right choice depends entirely on your topic and the story you’re trying to tell.

Here’s a breakdown of the most common approaches to help you decide which one best fits your research narrative.

Choosing Your Literature Review Structure

| Structure Type | Best For | Potential Pitfall |

|---|---|---|

| Thematic | Most dissertations. Organizing by key concepts, themes, or debates allows for strong synthesis and shows a deep understanding of the field's conversations. | Can be tricky to organize if your themes overlap significantly. Requires a very clear outline from the start. |

| Methodological | Topics where the how is as important as the what. Useful for comparing findings from quantitative vs. qualitative studies or highlighting gaps in research methods. | Might feel disconnected if not tied back to a central research question. Can accidentally focus too much on methods and not enough on findings. |

| Chronological | Showing the historical evolution of a concept or theory. Great for tracing how an idea has developed, been challenged, and changed over decades. | Very easy to fall into the trap of just listing studies in order ("First X found this, then Y found that...") without any real synthesis. |

Choosing the right structure is half the battle. A thematic approach is usually the strongest, as it forces you to think in terms of ideas rather than just listing authors.

A critical part of learning how to write a literature review for a dissertation is recognizing that your primary goal is to tell a story. Each paragraph, each transition, and each thematic section should build on the last, creating a logical path that culminates in the justification for your own research.

From Annotated Notes to a Synthesis Matrix

Moving from a stack of individual notes to a synthesized argument can feel overwhelming. This is where visual tools are your best friend.

One of the most powerful tools I've seen students use is a synthesis matrix. It’s just a simple table where you can map out what different authors say about your key themes, all in one place.

This kind of thinking—zeroing in on high-quality, relevant sources—is the bedrock of a strong synthesis. You can't build a coherent argument on a shaky foundation.

Once you have your key themes (which will probably become your subheadings), create a table. List your themes across the top row and your key sources down the first column. In each box, jot down a quick summary of what that specific author contributes to that theme. Suddenly, you'll see the patterns, contradictions, and gaps pop right off the page.

Situating Your Work Within Broader Debates

A big part of a modern dissertation is explicitly using a theoretical or conceptual framework to ground your literature review. This isn't just academic fluff; it proves your argument is part of an established scholarly conversation.

A 2022 study found that between 2010 and 2020, the number of STEM articles referencing these frameworks shot up by more than sevenfold. This signals a huge shift—supervisors now expect you to do more than summarize. You need to position your research within an established paradigm to give it weight. You can read the full research about this trend in academic writing.

So, what does this mean for you? You need to identify the core theoretical debates in your field and make it crystal clear where your research stands. Are you:

- Confirming a theory with fresh evidence?

- Extending a theory by applying it to a new context?

- Challenging a theory with findings that just don't fit?

Making this stance clear from the get-go is what transforms your review from a passive summary into a critical, assertive piece of scholarship. As you bring in the work of others, it's absolutely crucial to represent their ideas accurately but in your own words. For some practical tips, check out our guide on how to paraphrase without plagiarizing—a must-have skill at this stage.

By clearly articulating your position within these broader academic dialogues, you elevate your literature review from a simple summary to a genuine contribution to your field.

Drafting Your Review with a Critical Voice

Alright, you’ve wrestled your sources into a coherent map. Now comes the hard part: actually writing the thing. This is where you shift from being a research collector to a genuine scholar. Your job is to move beyond simply reporting what others have found and start building your own argument.

The single biggest pitfall at this stage is what I call the "laundry list" review. It’s where you just summarize one paper after another without ever connecting the dots. Don't do that. You are the guide, and it's your voice that needs to interpret, critique, and weave these disparate studies into a compelling narrative.

Nailing the Introduction and Conclusion

Your introduction is more than just a warm-up. It’s a roadmap for your reader, setting the stage for the entire chapter. A good one needs to clearly establish the context, define the scope of your review, and state the argument you’re about to make.

A strong literature review intro usually does these four things:

- It gives a quick overview of the broader research field to get everyone on the same page.

- It clearly states the specific focus of your review—what’s in and what’s out.

- It outlines the thematic structure you'll be following.

- It ends with a thesis statement that points directly to the research gap your dissertation is going to fill.

The conclusion, on the other hand, isn't just a summary. It's your closing argument. This is where you powerfully reinforce the research gap you’ve spent the chapter establishing. It’s your last chance to convince the reader that your study isn’t just interesting, but absolutely necessary.

Finding Your Academic Voice

Developing a critical voice is about shifting from description to analysis. It's the difference between "Smith found X" and "Smith's findings challenge the prevailing theory by..." You’re not just a reporter. You are an interpreter of the academic landscape.

This is a non-negotiable skill. A 2023 scientometric study revealed that 75% of dissertations in Library and Information Science now include a dedicated research methods section, and 60% of those justify their choices in detail. This trend toward methodological rigor and critical evaluation is now the standard across most disciplines. You can dig into the findings on dissertation methodologies to see how this plays out.

To start injecting your own voice, try using sentence starters that force you to think critically:

- "While Jones (2021) makes a compelling case, their study overlooks the critical role of..."

- "A key tension in the literature emerges when comparing the work of... and..."

- "This finding is significant because it extends our understanding of..."

- "However, the methodology used by Chen (2019) raises questions about the generalizability of these results."

Phrases like these immediately shift the focus from what others said to what you think about what they said. It puts you back in the driver's seat.

Your academic voice is your scholarly persona. It should be confident, analytical, and fair. You're stepping into a conversation with other experts, so your tone should be one of respectful critique, not aggressive takedowns.

Building Strong, Argument-Driven Paragraphs

Think of each paragraph as a mini-argument. It should revolve around one clear idea, which you’ll state right up front in a topic sentence. The rest of the paragraph is for your evidence—pulled from your sources—and your analysis of that evidence.

A simple but incredibly effective paragraph structure looks like this:

- Claim: Start with your own assertion or interpretation. This is your topic sentence.

- Evidence: Back it up with findings or arguments from one or more of your sources.

- Analysis: Explain how that evidence proves your claim and tie it back to the bigger argument you're making in the review.

Following this structure ensures that your voice is always leading the discussion.

Using Signposts to Guide Your Reader

Signposting is just using transitional words and phrases to guide your reader through the twists and turns of your argument. Without them, your writing can feel choppy and confusing, even if the ideas themselves are solid. They're the glue that holds everything together.

Here are a few examples of signposting in action.

| Purpose | Example Phrases |

|---|---|

| Introducing a theme | "A central theme running through the literature is..." |

| Showing contrast | "In contrast," "On the other hand," "However..." |

| Adding a point | "Furthermore," "In addition," "Similarly..." |

| Concluding a section | "Therefore," "In summary," "These findings suggest..." |

When you use these phrases strategically, you create a coherent narrative that's easy to follow. Drafting with a critical voice is how you turn a pile of research into a powerful, argument-driven piece of scholarship.

Revising Your Work to Ensure Coherence and Clarity

Your first draft is a huge milestone, but don't celebrate just yet. The revision process is where your literature review truly transforms from a jumble of notes and sources into a polished, persuasive piece of scholarship.

This isn't just about fixing typos. It’s a strategic process of sharpening your argument, strengthening your voice, and making sure your writing is as clear as it is compelling.

I find it helpful to think of revision in two phases. First, you tackle the big-picture stuff—the macro-level issues. After that, you can zoom in on the sentence-level details, or the micro-level edits. This approach stops you from getting lost in comma splices when an entire section’s argument needs a complete rethink.

Starting with the Big Picture Revisions

Macro-level editing is all about the architecture of your literature review. At this point, you’re not reading for grammar. You're reading for logic, structure, and flow. The goal is to ensure your chapter tells a coherent story that naturally leads the reader to your research gap.

Print out your draft and grab a highlighter. Seriously, get it off the screen. As you read, ask yourself these tough questions:

- Is my core argument obvious? Can someone easily tell what I’m arguing about the current state of the literature?

- Does the structure actually work? Do my thematic sections flow into each other, or do they feel like separate, disconnected essays?

- Have I truly synthesized the material? Did I weave sources together to discuss concepts, or did I just line up a series of book reports? (e.g., "Smith says this... Jones says that...").

- Is my voice present? Does my critical perspective come through, or does it sound like a passive summary of other people's work?

This is also the time to assess the overall narrative. Does the introduction set the stage properly? Does the conclusion powerfully underscore why your study is necessary? If a section feels like a detour, it probably is. Be ruthless. Cut or move anything that doesn't directly serve your central argument.

An effective literature review doesn't just present information; it makes an argument about that information. Your revision should focus on making that argument impossible to miss.

Honing Your Prose with Micro-Level Edits

Once you’re confident in the structure, it’s time to get granular. Micro-level editing is about the craft of writing—the individual sentences and word choices that make your work readable. This is where you polish your prose until it shines.

A huge part of this is just aiming for clarity and conciseness. Academic writing gets a bad rap for being dense and convoluted, but the best scholarship is actually crystal clear. Hunt down jargon, kill your darlings (and your wordiness), and break up those long, winding sentences into shorter, more direct ones.

Your goal here is to achieve a strong sense of cohesion, where every sentence flows smoothly from the one before it. Strong transitions and clear topic sentences are your best friends. If you want a deeper dive, there's a great breakdown of what cohesion is in writing that offers some practical tips.

Here’s a trick that always works: read your work aloud. Your ears will catch awkward phrasing and clunky sentences that your eyes will skim right over. If you stumble over a sentence when you say it, your reader definitely will.

A Practical Revision Checklist

To guide your final pass, here’s a checklist of common pitfalls I see all the time. Fixing these will elevate the quality of your writing significantly.

- Check for a Consistent Academic Tone

- Action: Get rid of casual language, clichés, and contractions. Make sure your tone is consistently analytical and authoritative.

- Eliminate Passive Voice

- Action: Do a search for phrases like "was done by" or "it was found that." Flip them into the active voice (e.g., "Smith (2022) found that...") to make your writing more direct.

- Verify Citation Accuracy

- Action: This is tedious but non-negotiable. Meticulously check every single in-text citation against your reference list. Ensure names are spelled correctly, dates match, and your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) is perfect.

- Strengthen Signposting

- Action: Look at how you move between paragraphs and sections. Do you need to add or improve your signposting language ("However," "In contrast," "Furthermore") to guide the reader through your argument?

- Refine Word Choice

- Action: Replace vague words like "thing," "aspect," or "interesting" with precise, descriptive language. Make sure you're using key technical terms correctly every time.

This final polish is what separates a good literature review from a great one. By dedicating real time to both the big picture and the tiny details, you ensure your work is not only intellectually sound but also a pleasure to read.

Common Questions That Come Up When Writing a Literature Review

Even with a great plan, writing a dissertation lit review can feel a bit murky. A few questions pop up again and again for students, and getting them answered can give you the confidence to push forward.

How Many Sources Do I Actually Need?

Honestly, there's no magic number. The right amount depends entirely on your field, the specifics of your topic, and just how much research is already out there. A history dissertation might lean on well over a hundred sources, while a super-niche scientific study could be perfectly thorough with far fewer.

Instead of obsessing over a number, you should be aiming for saturation.

What’s that? It’s the point where you start seeing the same names, same studies, and same arguments cited in every new paper you find. When your searches stop turning up genuinely new ideas, you're probably getting close.

The real goal isn't to hit a quota. It's to prove you have a rock-solid grasp of the key theories, the foundational studies, and the current debates happening in your corner of the academic world.

A common trap is thinking more is always better. A review that masterfully weaves together 50 highly relevant sources is infinitely stronger than one that just lists 150 loosely related ones. Focus on quality, not quantity.

What's the Difference Between a Lit Review and an Annotated Bibliography?

This one's a big deal. They both involve digging into sources, but their purpose and final form couldn't be more different.

An annotated bibliography is basically a list. For each source, you write up a full citation and follow it with a short paragraph—the annotation—that summarizes and critiques that single work. It's a collection of individual, stand-alone evaluations. Think of it as a series of disconnected book reports.

A literature review, on the other hand, is a single, flowing essay. It synthesizes ideas from many sources to build a coherent argument. You don't organize it source-by-source; you organize it by themes, concepts, or debates to tell the story of the research field. The whole point is to use that story to show why your study is necessary.

How Do I Know When I've Read Enough?

It's completely normal to feel like you're drowning in an endless sea of articles. You'll know you’re getting to the end of the heavy reading phase when you hit that "point of saturation" we just talked about.

You’ll start to notice a few things:

- New articles you find are just citing sources you’ve already read and analyzed.

- You can pretty much predict a paper’s main arguments just by looking at the author and title.

- You can explain the major theories and key findings in your niche without constantly checking your notes.

Once you hit that point, your job shifts. You’re no longer just discovering information; you're moving on to the much harder work of weaving it all together into a critical narrative. You've gathered your evidence. Now it's time to build your case.

Tired of your AI-generated drafts sounding robotic? Natural Write is a free tool that instantly humanizes your text, making it sound clear, natural, and authentic while bypassing AI detectors. Perfect for students and writers who want to refine their work without losing their original ideas. Polish your next paper with confidence at https://naturalwrite.com.