Mastering Essay Structure and Examples

September 10, 2025

A solid essay structure is your roadmap to a top grade. It breaks the entire writing process down into three core parts: a compelling introduction, well-supported body paragraphs, and a memorable conclusion. This simple framework is the key to transforming a jumble of ideas into a powerful, coherent argument.

The Blueprint for a Winning Essay

Staring at a blank page can feel pretty intimidating. A lot of writers think structure is just some rigid formula that kills creativity, but it’s better to think of it as a blueprint for building a clear and convincing argument. Honestly, mastering this basic organization is the fastest way to improve the clarity and impact of your writing.

This blueprint will be our guide for the rest of this post, setting you up for success right from the very first sentence.

The Three Core Components

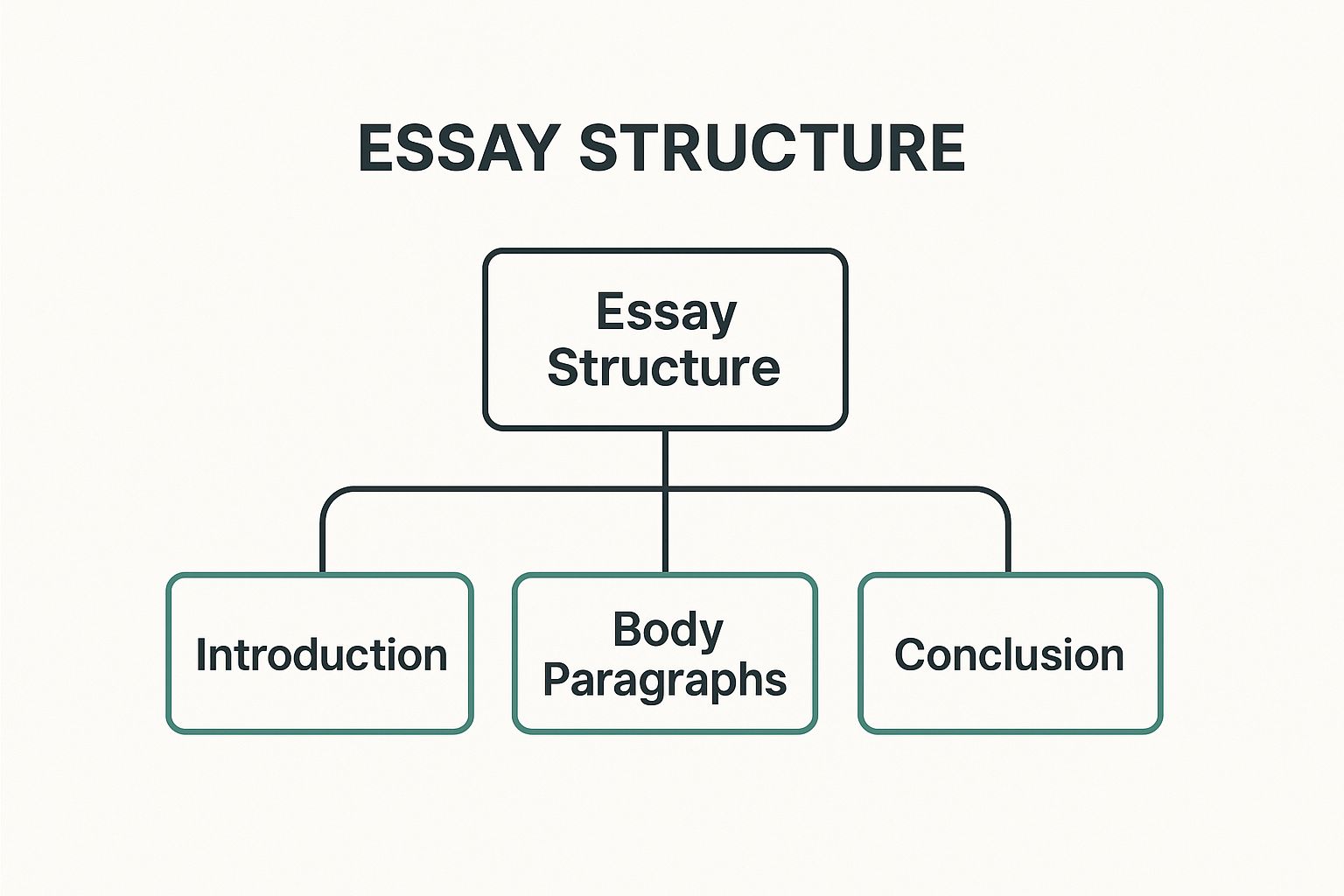

Think of it like building a house. The introduction is the foundation that sets the stage. The body paragraphs are the walls that hold up your ideas. And the conclusion? That's the roof that ties everything together. Each part has its own job, but they all work in harmony to create something impressive.

At its heart, this is what academic essays are all about. You have an introduction, a body that develops your argument, and a conclusion that wraps it all up. The central piece holding it all together is the thesis—a clear, arguable statement that you'll back up with evidence.

This image gives you a simple, top-down look at how these components fit together.

As you can see, the body paragraphs are the real workhorses of the essay. They carry the weight of your entire argument.

To give you a quick cheat sheet, here’s a breakdown of what each part of the essay is responsible for.

The Three Pillars of Essay Structure

| Essay Part | Primary Function | Key Components to Include |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | Grab the reader’s attention and state the main argument. | Hook, background context, thesis statement. |

| Body Paragraphs | Present evidence and develop the argument. | Topic sentence, evidence/examples, analysis, transition. |

| Conclusion | Summarize the argument and provide a final takeaway. | Restated thesis, summary of main points, final thought. |

Keep these pillars in mind as you write, and you'll have a strong, logical foundation for any essay you tackle.

Why Structure Is Your Greatest Ally

A good structure does more than just organize your thoughts—it walks your reader through your reasoning, step by step. Without it, even the most brilliant ideas can get lost in a confusing mess.

A strong structure ensures your argument is not just stated, but proven. It transforms a collection of facts into a persuasive narrative that leads the reader to your intended conclusion.

This isn't just true for essays. The same logic applies to almost any kind of persuasive communication. For example, a well-designed startup pitch deck template also relies on a logical flow to win over its audience.

Ultimately, a good blueprint makes your job as a writer easier and the reader’s experience far more impactful.

Crafting an Introduction That Captivates

Your introduction is your first impression. And sometimes, it's your only impression.

Think of it like the opening scene of a movie. It has to hook the audience immediately and make them lean in, wondering what’s going to happen next. A great introduction does three things, and it does them well. It grabs the reader, gives them just enough context to get their bearings, and then presents a clear, debatable thesis statement.

Let's break down how to nail each of these elements, with some solid examples to show you what I mean.

The Art of the Hook

The first sentence of your essay has exactly one job: make someone want to read the second sentence. That’s your hook. A generic opening signals a generic essay, so you want to start with something that sparks a little curiosity or maybe even challenges what the reader thinks they know.

Here are a few proven ways to do it:

- A Surprising Statistic: A powerful number can instantly signal that your topic matters and that you know what you’re talking about.

- A Provocative Question: Ask something that gets the reader thinking and engages them right from the start.

- A Relevant Quotation: A great quote can frame your argument and connect it to a bigger conversation.

- An Anecdote: A short, relevant story makes your topic feel more personal and concrete.

For an essay on remote work, you could use a surprising statistic to really grab attention. Something like this:

Example Hook: While many companies feared a drop in productivity, a recent study found that remote employees are 47% more productive than their in-office counterparts.

See how that works? It immediately makes you curious and sets up a discussion that might challenge common assumptions.

Providing Essential Context

Okay, you've hooked them. Now what?

Before you jump into your main argument, you need to give your reader a little bit of background. This isn’t the place for a deep dive; it’s just about setting the scene. What does someone need to know to understand why your thesis is important? Keep it brief—just a couple of sentences to bridge the gap between that opening hook and your main point.

Following our remote work hook, the context could look like this:

Example Context: The global shift to remote work, accelerated by the pandemic, has fundamentally changed the corporate landscape. This transition has sparked intense debate about its long-term effects on company culture, employee well-being, and overall business performance.

This smoothly connects the initial statistic to the core debate the essay is about to tackle.

Forging a Powerful Thesis Statement

Now for the most important sentence in your entire essay: the thesis statement.

This is the backbone of your argument. It’s a clear, concise declaration of the claim you’re going to spend the rest of the essay proving. It always sits at the end of your introduction.

A weak thesis just states an obvious fact. A strong one is debatable, specific, and analytical. It takes a stand.

Let’s look at the difference.

Weak Thesis (Just a fact):

- "The internet has changed how people access information." (Well, yeah. Who would argue with that?)

Strong Thesis (An actual argument):

- "While the internet has democratized access to information, its reliance on algorithms has created echo chambers that pose a significant threat to critical thinking and societal cohesion."

That second one is a real argument. It presents a clear, debatable position that the rest of the essay now has to back up with evidence. It gives the reader a roadmap, showing them exactly what you plan to prove and how you’ll do it. That's the foundation of a truly compelling essay.

Building Your Argument with Strong Body Paragraphs

If your introduction is the blueprint, the body paragraphs are the load-bearing walls. This is where the heavy lifting happens—where you actually convince your reader that your argument holds up. Think of each paragraph as a self-contained unit designed to prove one specific point.

Without strong, well-supported body paragraphs, even the most brilliant thesis will crumble under its own weight. The trick is to be methodical. You need a reliable system to build each paragraph so your argument flows logically from one point to the next, building a case that’s impossible to ignore.

Mastering the P.E.E.L. Method

One of the best frameworks out there for writing a solid body paragraph is the P.E.E.L. method. It’s a simple acronym that forces you to cover all your bases, turning a simple claim into a well-defended piece of your argument.

It’s basically a four-step recipe for a persuasive paragraph:

- Point: Start with a clear topic sentence that makes your claim.

- Evidence: Back it up with specific facts, quotes, or data.

- Explanation: Analyze the evidence. Explain how it proves your point.

- Link: Connect it all back to your main thesis and set up the next idea.

This structure ensures every paragraph has a clear purpose. It keeps you from just dropping in facts without explaining why they matter—a classic mistake that can sink an otherwise good essay.

Breaking Down Each Step with Examples

Let’s walk through the P.E.E.L. method using a sample thesis: "While remote work offers flexibility, its negative impact on team collaboration and innovation outweighs the benefits for creative industries."

1. Point (Your Topic Sentence)

The first sentence of your paragraph needs to make a sharp, focused point that supports your thesis. It’s a signpost for your reader, telling them exactly what this section is about.

Bad Example: "Remote work can be difficult for teams." (Too vague. It doesn’t make a real claim.)

Good Example: "The lack of spontaneous, in-person interactions in remote settings significantly hinders the collaborative brainstorming essential for creative innovation."

See the difference? The good example is specific, arguable, and clearly supports a piece of the main thesis.

2. Evidence (The Proof)

Now, you need to bring in the proof. Your evidence can be a statistic, an expert quote, a study, or a concrete example. This is what gives your argument credibility.

Example Evidence: "For instance, a study from a prominent business school found that teams who switched to fully remote work saw a 20% decline in cross-departmental conversations, which are often the source of novel ideas."

This simple statistic adds weight to your claim, elevating it from an opinion to a supported fact.

3. Explanation (The Analysis)

This is the most important—and most often skipped—step. Your explanation is where you connect the dots for the reader. Don't just present the evidence; analyze it. Explain how it proves the point you made in your topic sentence.

Example Explanation: "This 20% reduction isn't just a number; it represents the loss of casual coffee-break chats and impromptu whiteboard sessions where real breakthroughs happen. Without those unplanned collisions of ideas, teams become siloed, the creative friction disappears, and the work becomes more predictable and less imaginative."

This analysis digs into the "so what?" It tells the reader why that 20% figure actually matters.

4. Link (The Connection)

Finally, you need to link this paragraph's idea back to your overall thesis. A good link also smoothly transitions the reader to your next point.

Example Link: "Therefore, the erosion of spontaneous collaboration directly undermines the innovative engine of creative industries, highlighting a critical flaw in the remote-first model. This problem of creative stagnation is further compounded by the challenges of mentorship..."

This sentence wraps up the current point and perfectly tees up the topic of the next paragraph (mentorship).

By consistently applying the P.E.E.L. method to your essay structure and examples, you’ll build a robust and persuasive case, one solid paragraph at a time. After you've drafted your paragraphs, the next step is to polish them. For more on that, check out our guide on essential essay editing tips.

Let's Pull Apart a Full Essay Example

Theory is one thing, but seeing how an essay actually comes together is where the lightbulbs really go on. To close the gap between knowing the rules and actually using them, we're going to deconstruct a complete essay, piece by piece. This walkthrough will show you the "why" behind the writing choices.

We'll look at everything, from the opening hook that grabs your attention to the final, memorable conclusion. By breaking down a full essay, you’ll see exactly how a strong thesis statement acts as a roadmap for the entire argument and how each body paragraph uses evidence to back up its claims. This is a skill that transfers, too. Just like with essays, analyzing grant writing samples can offer incredible insights into what makes persuasive writing work.

The Complete Sample Essay

Let's dig into an essay that takes a specific stance on technology's role in modern education.

Essay Title: Beyond the Smartboard: The Double-Edged Sword of Technology in K-12 Classrooms

Full Essay Text:

While many herald educational technology as a great equalizer, its implementation often deepens existing educational disparities rather than closing them. The initial promise of digital tools was to democratize access to information, creating a level playing field where every student, regardless of background, could thrive. However, this optimistic vision overlooks the critical roles of digital literacy, equitable home access, and effective teacher training. Without addressing these foundational issues, technology in the classroom becomes less of a bridge and more of a barrier, inadvertently amplifying the advantages of privileged students while leaving others further behind.

One of the most significant hurdles is the assumption of universal digital literacy. Simply placing a tablet in a student's hands does not equip them with the critical thinking skills needed to navigate the digital world effectively. Students from higher-income households are more likely to have consistent exposure to technology in a structured, educational context at home, fostering these skills from an early age. Consequently, when technology is introduced in school, these students can immediately leverage it for advanced research and creative projects, while their less-privileged peers are still grappling with basic functionalities. This initial gap in digital fluency creates a classroom dynamic where technology rewards the already-prepared, widening the performance gap.

Furthermore, the "homework gap" highlights a stark inequity in out-of-school access to technology and reliable internet. A significant percentage of students from low-income families lack consistent broadband access at home, making it difficult, if not impossible, to complete online assignments, conduct research, or collaborate on digital projects. While schools may provide devices, their utility plummets once students leave campus. This disparity forces students without home access to rely on public libraries or other less-than-ideal solutions, creating immense stress and putting them at a distinct disadvantage compared to classmates who have a connected, quiet place to work.

Ultimately, the promise of educational technology can only be realized when its implementation is paired with robust support systems. Instead of simply focusing on acquiring the latest gadgets, school districts must invest heavily in comprehensive teacher training to ensure educators can integrate these tools pedagogically. Simultaneously, public and private initiatives must work to close the digital divide by expanding affordable broadband access. Until technology is implemented equitably, with a focus on skill-building and access for all, it will remain a double-edged sword that reinforces the very inequalities it was meant to solve.

Introduction Breakdown

The introduction is your first impression, and this one nails it by doing three things perfectly.

- The Hook: It starts with a popular idea ("technology as a great equalizer") and then immediately pokes a hole in it. That creates instant tension and makes you want to read more.

- Context: It quickly lays out the core problems: digital literacy, home access, and teacher training. No fluff, just the key issues.

- Thesis Statement: The last sentence delivers the main argument loud and clear: "Without addressing these foundational issues, technology in the classroom becomes less of a bridge and more of a barrier..."

This structure does a fantastic job of setting the stage. It gives the reader a clear map of where the essay is headed, moving smoothly from a big, general idea to a sharp, specific claim.

Body Paragraph Analysis

Think of each body paragraph as a mini-argument that supports the main thesis. Let's look at the first one to see how it works.

- Point (Topic Sentence): "One of the most significant hurdles is the assumption of universal digital literacy." This sentence makes a clean, focused claim that ties directly back to the thesis.

- Evidence and Explanation: The paragraph then explains why this is a problem, pointing out how kids from higher-income homes often have a head start. It contrasts their experience with their peers, giving a logical breakdown of the issue.

- Link: The final phrase, "widening the performance gap," explicitly connects the point about digital literacy back to the essay's core argument about technology making inequality worse.

This clear, structured approach is repeated in the second body paragraph, which tackles the "homework gap." This ensures the essay’s argument builds momentum logically, moving persuasively from one point to the next.

Finally, the conclusion wraps everything up. It restates the thesis with more confidence (now that it's been proven) and leaves the reader with a powerful final thought.

Writing a Conclusion That Resonates

Too many great essays just fall apart in the final paragraph. After pouring all that energy into a killer intro and solid body paragraphs, it's tempting to just slap a summary on the end and call it a day.

But that’s a huge mistake. Your conclusion is your last chance to speak to your reader, and it’s what will stick with them long after they’ve put your essay down.

Think of it this way: your introduction made a promise, and your body paragraphs delivered the evidence. Your conclusion is where you get to stand up and confidently say, “I proved my point.” It doesn’t just rehash everything you’ve already said; it pulls all those ideas together to show the reader the bigger picture you’ve just painted.

A strong conclusion doesn’t just end the essay. It makes it feel finished—and important.

The Three Core Jobs of a Conclusion

A powerful conclusion has three critical jobs to do, each one building on the last. Nailing these is what takes an essay from just "good" to truly great.

Here’s what you need to do:

- Revisit Your Thesis: You start by restating your thesis, but not word-for-word. Say it again, but this time with the confidence that comes from having proven it.

- Synthesize Your Main Points: Briefly touch on your key arguments. The goal isn't to make a list, but to show how they all connect and support your main idea.

- Answer the “So What?” Question: This is the most important part. You have to leave your reader with a final, powerful thought that shows why any of this matters.

A great conclusion gives the reader a sense of closure while also leaving them with something new to think about. It’s the difference between ending a conversation with "goodbye" and ending it with a thought-provoking question that lingers.

Answering the "So What?" Question

The "so what?" is your mic-drop moment. It’s where you explain why your argument matters beyond just the pages of your essay. It answers the reader’s unspoken question: "Okay, you've convinced me... so what?"

There are a few effective ways to land this final punch:

- Suggest Broader Implications: Connect your topic to a larger issue in society, culture, or your field.

- Propose a Call to Action: What should the reader do, think, or believe now that they’ve read your essay?

- Look to the Future: What might happen next? Hint at the future direction or impact of your topic.

- Pose a Provocative Question: Leave your reader with a compelling question that makes them keep thinking.

Let’s see how this transforms a conclusion from weak to strong. We'll use this thesis: "While the internet has democratized access to information, its reliance on algorithms has created echo chambers that pose a significant threat to critical thinking."

Weak Conclusion Example:

In conclusion, the internet provides a lot of information, but algorithms create echo chambers. These echo chambers are bad for critical thinking, as I have shown in my body paragraphs.

This is just a flat summary. It’s boring, and it adds nothing new.

Strong Conclusion Example:

It is clear that while the internet promised a universe of information, algorithmic curation has instead built invisible walls around our curiosity. By reinforcing our existing beliefs, these echo chambers don’t just limit our access to diverse perspectives; they actively erode the foundations of critical thought. If we fail to consciously seek out dissenting views, are we prepared for a future where our opinions are no longer our own, but merely echoes of a code designed to keep us comfortable?

See the difference? This version restates the thesis with fresh language, synthesizes the core idea (erosion of critical thought), and ends with a powerful question that answers the "so what?" It leaves a real impression.

For a deeper dive into these strategies, check out our guide on how to write a conclusion paragraph that truly stands out.

Common Questions About Essay Structure

We’ve walked through the blueprint of a great essay, from the hook in the introduction to the final thought in the conclusion. But even with a solid plan, real-world questions always pop up.

Think of this section as your troubleshooting guide. We’ll tackle the "what ifs" and "how-tos" that trip up even experienced writers. My goal here is to clear up any lingering confusion so you can apply your knowledge of essay structure and examples with confidence.

How Long Should Each Section of My Essay Be?

While there isn't a single magic formula, a great rule of thumb is the 10-80-10 rule. It’s a simple, reliable way to balance your essay and make sure your core argument gets the attention it deserves.

Here's the breakdown:

- Introduction: Aim for roughly 10% of your total word count.

- Body Paragraphs: This is the heart of your essay. Dedicate around 80% of your word count here.

- Conclusion: The final 10% is for wrapping everything up.

So for a 1,000-word essay, that means a 100-word intro, 800 words for the body, and a 100-word conclusion. The key takeaway is that the body is the engine—it should always be the most substantial part. Of course, always double-check your assignment for any specific instructions from your professor first.

What Is the Difference Between a Thesis and a Topic Sentence?

This is a fantastic question because it gets right to the core of how a strong, organized argument is built. Think of your essay's structure like a hierarchy.

Your thesis statement is the general of the army. It’s the single, controlling idea for the entire essay. Every sentence you write should, in some way, serve this one central command.

A topic sentence, on the other hand, is like a captain leading a single platoon. It states the main point for just one body paragraph. Each topic sentence is a mini-argument that directly supports and proves a small piece of your overarching thesis.

In short, your thesis governs the whole essay, while each topic sentence governs just one paragraph. A strong essay is one where all the "captains" (topic sentences) are clearly and effectively following the "general's" orders (the thesis).

Can I Use First-Person Pronouns Like “I” in an Essay?

The answer really depends on the subject you're writing for and, most importantly, your instructor’s preference. The rules aren't universal, and they've been shifting over the years.

In many humanities fields, like literature or philosophy, using "I" is becoming much more common and is often encouraged. It helps you state your argument directly and honestly (e.g., "I argue that..."). There’s no ambiguity about where you stand.

However, in most STEM and social science courses, the objective, third-person voice is still the standard. The focus is on the data and evidence, not the researcher's personal opinion.

The safest bet is always to check your assignment instructions or just ask your instructor. When in doubt, it’s usually better to stick to the third person by phrasing things objectively, like "The evidence suggests..." instead of "I think the evidence suggests..."

How Many Body Paragraphs Should an Essay Have?

The classic five-paragraph essay (with its three body paragraphs) is a fantastic starting point for learning structure. It's perfect for shorter assignments. But you should never feel trapped by it.

The number of body paragraphs you need should be driven by the complexity of your argument, not some rigid formula. A more detailed thesis will naturally have more points to prove, which means it will need more body paragraphs to develop those points properly.

Think of it this way: each distinct idea supporting your thesis deserves its own paragraph. If you cram too many ideas into one, your argument gets messy. If you stretch one small idea across several paragraphs, your argument feels thin and weak.

For longer research papers, it’s completely normal to have five, ten, or even more body paragraphs. The real goal is to develop each point fully, not just to hit an arbitrary number. The length of your paper is also a crucial factor, and to get more clarity on this, our detailed post on how many words an essay should be offers some great guidance.

After crafting your essay with the perfect structure, the final step is ensuring your writing sounds polished and natural. Natural Write transforms AI-generated or rough drafts into clear, human-like text that bypasses AI detectors. Refine your tone, improve readability, and submit your work with confidence. Try it for free at https://naturalwrite.com.