How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis Like an Expert

December 11, 2025

Writing a rhetorical analysis isn't about summarizing a text. It's about dissecting it to figure out how an author builds their argument.

You're basically becoming a detective, investigating the persuasive techniques at play by looking at the relationship between the speaker, the audience, and the message itself.

So, What Is a Rhetorical Analysis Really Asking You To Do?

Before you even think about writing, you have to get the main goal straight. A rhetorical analysis is not the place to argue with the author's point. Your job is to break down the machinery behind the words—all the little choices the author made to convince a specific audience. You need to be an active critic, not just a passive reader.

Think of it like watching a magician. Your goal isn’t just to be amazed by the trick. It’s to figure out how they pulled it off. What sleight of hand did they use? Which props were essential? How did they direct your attention away from the secret? That’s the exact mindset you need for a rhetorical analysis.

Getting in the Right Headspace

The whole key is shifting your focus from the what (the topic) to the how (the strategy) and the why (the intended effect). This simple change in perspective turns you into an investigator of persuasive communication.

Every piece of writing, from a presidential speech to a simple Instagram ad, is designed to do something. Your task is to uncover that purpose by examining the tools the creator used. This isn't just guesswork; it's a structured way to evaluate how an argument is built. In almost any college writing course, a strong analysis will nail a few key things:

- Figuring out the context: What was going on when this was written?

- Spotting the strategies: What specific techniques are being used, like emotional appeals or hard data?

- Making a claim: What’s your thesis about how well (or not) these strategies worked?

In fact, it’s standard in university writing programs for 75-80% of students to learn how to weave in logical appeals with facts and data. It just goes to show how central evidence is to this type of writing. If you want to dive deeper into this framework, our guide on what rhetoric in writing truly means is a great place to start.

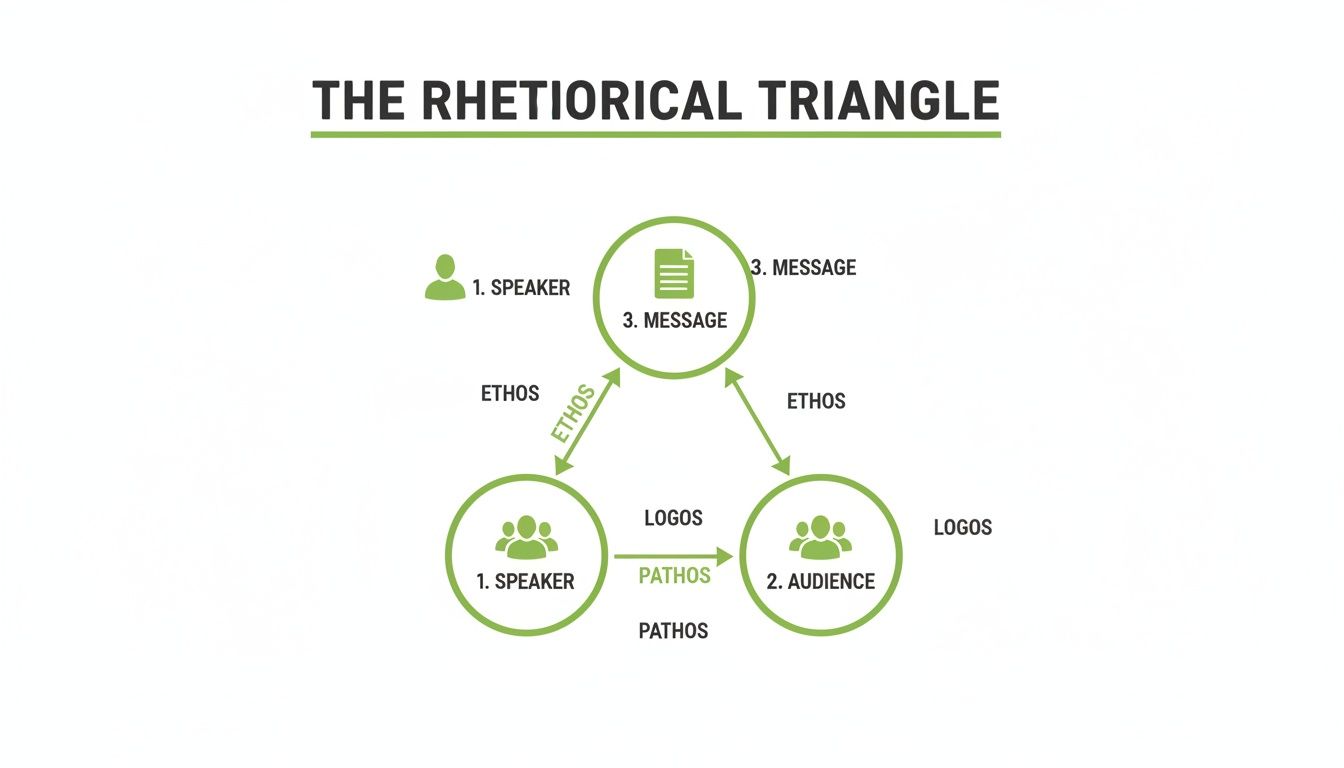

Unpacking the Rhetorical Triangle

The best starting point for any analysis is the rhetorical triangle. It's a classic concept that shows how three core elements of persuasion—ethos, pathos, and logos—are always in a dynamic dance with each other.

Understanding this triangle is non-negotiable. It’s the framework that holds every persuasive argument together. By analyzing how these three appeals work in harmony (or conflict), you unlock the secret to any text's persuasive power.

These three appeals are your primary clues for your investigation.

Simply put, Ethos is all about the speaker’s credibility and character. Pathos is the appeal to the audience’s emotions. And Logos is the appeal to logic and reason.

The table below breaks it down for quick reference.

The Rhetorical Triangle At a Glance

| Rhetorical Appeal | What It Is | Key Questions to Ask |

|---|---|---|

| Ethos | The appeal to credibility and character. | Does the author seem trustworthy? What are their qualifications? Do they have good intentions? |

| Pathos | The appeal to emotion. | How does the text make the audience feel? Does it use stories, imagery, or loaded words to stir up emotions? |

| Logos | The appeal to logic and reason. | Does the argument make sense? Is it backed by facts, statistics, or evidence? Is the reasoning sound? |

A sharp rhetorical analysis always looks at how an author balances these appeals to hit their mark. By focusing on this dynamic, you move beyond just summarizing and start offering real critical insight.

Getting Your Text Ready for Analysis

A powerful rhetorical analysis isn’t built on guesswork; it’s built on preparation. Before you even think about a thesis, you have to become an investigator. This means shifting from a passive reader to an active analyst, ready to deconstruct how the text works.

Your first read-through should be about getting the lay of the land. Don't get bogged down in the details just yet. The goal here is simple: understand the author's main point and the overall vibe of the piece.

Once you’ve got a feel for the core argument, the real work begins. It’s time to go beyond basic highlighting and get systematic.

How to Actively Annotate

Passive highlighting isn’t going to cut it. Active annotation is like having a conversation with the text. To really dig in, you'll want to use some effective note-taking methods that help you see the patterns. You're creating a visual map of the author's persuasive moves.

A simple color-coding system is a great place to start. Just assign a color to each of the three main rhetorical appeals.

- Green for Logos: Highlight any facts, stats, logical chains of reasoning, or data the author presents.

- Pink for Pathos: Mark any words, phrases, or stories clearly meant to stir up an emotional response.

- Blue for Ethos: Underline anything that builds the author's credibility—credentials, appeals to authority, or attempts to build trust.

This technique instantly shows you which appeals the author leans on most. As you go, scribble questions in the margins. Ask things like, "Why this specific statistic?" or "What emotion is this story trying to make me feel?"

Uncover the Context (SOAPSTone)

Beyond the text itself, you need to understand the situation that created it. The SOAPSTone method is a fantastic tool for this. It’s a simple acronym that helps you break down all the key contextual elements shaping the author's choices.

The rhetorical situation is all about the relationship between the speaker, their message, and the audience.

Think of it this way: a truly persuasive message has to balance the speaker's credibility (ethos), the audience's emotions (pathos), and the logical argument (logos).

Here’s how to apply SOAPSTone to your text:

- Speaker: Who is creating this? What do we know about their background, biases, or credentials?

- Occasion: What prompted this to be written? Was it a response to a specific event? What's the time and place?

- Audience: Who is this for? Think about their age, values, beliefs, and what they already know.

- Purpose: What does the speaker want the audience to think, feel, or do after reading this?

- Subject: What’s the main topic or central idea?

- Tone: What’s the author’s attitude? Are they sarcastic, formal, passionate, objective?

Answering these questions gives you a full profile of the rhetorical environment. This isn't just background info—it's crucial evidence that explains why the author made the choices they did.

Nail Down the Core Argument

This is the final, and maybe most important, step in your prep work. You need to summarize the author’s main argument in your own words.

This is a gut check. It’s not about just repeating their points.

If you can't clearly explain the main claim and its support in a few sentences, you don’t fully get it yet. Go back and read again until you can. This exercise forces you to distill the argument to its essence, which is the foundation your entire analysis will stand on. Once you've done this, you're no longer just a reader—you're a prepared investigator, ready to build a convincing case.

Finding Rhetorical Strategies Beyond the Big Three

Ethos, pathos, and logos are the heavy hitters of rhetoric, but they're just the beginning. If you stop there, you’re missing the details that make an argument truly persuasive. It’s like watching a movie and only paying attention to the plot—you miss the cinematography, the score, and the performances that bring it to life.

To really get under the hood of a text, you have to look at the author's stylistic choices. These subtler tools aren't separate from the big three; they’re what make them work. A sharp metaphor can ignite an emotional appeal (pathos), while formal, technical language can make a speaker sound more credible (ethos).

Analyzing Word Choice and Sentence Structure

Let's start small—with words and sentences. Every choice an author makes here is deliberate. Diction is all about the specific words they pick, while syntax is how they arrange those words.

Think about the difference between "fired" and "let go." One is direct and harsh; the other is a softer, corporate buffer. When you analyze diction, you’re asking why that specific word was used and what effect it has on the audience.

Syntax works the same way. It sets the rhythm. Long, flowing sentences can feel thoughtful and serious. Short, punchy ones create urgency, tension, or excitement.

Key Takeaway: An author’s diction and syntax are deliberate choices that control the pace, tone, and emotional texture of their argument. Don't just read the words; analyze why these specific words were arranged in this specific way.

Exploring Tone and Imagery

Tone is the author's attitude, and it seeps through their language. Are they being sarcastic? Sincere? Outraged? Pinpointing the tone is critical because it frames how the audience hears the entire message.

A politician might discuss a crisis with a somber, resolute tone to project seriousness. A comedian, on the other hand, might use a mocking tone to highlight the absurdity of the same situation.

Imagery is language that paints a picture by appealing to the five senses. It’s the difference between saying "it was a bad situation" and describing the "acrid smell of smoke" and the "wail of sirens." This is how an author makes an abstract idea feel real and immediate, turning up the dial on pathos.

Spotting Figurative Language

Figurative language offers a powerful shortcut to meaning. These are phrases that aren't meant to be taken literally but are used to make a point more memorable or impactful.

Keep an eye out for these:

- Metaphors and Similes: These draw comparisons to create a new layer of meaning. A simile uses "like" or "as" ("the economy is like a runaway train"), while a metaphor makes a direct comparison ("the economy is a runaway train").

- Personification: This gives human traits to non-human things, like saying "the wind whispered through the trees." It makes abstract concepts feel more alive and relatable.

- Hyperbole: This is just intentional exaggeration for effect. Think "I've told you a million times." The goal isn't to be literal but to add emphasis.

- Rhetorical Questions: These are questions that don't need an answer. They’re designed to make the audience think and guide them toward a specific conclusion. "Can we really afford to stand by and do nothing?" is a call to action in disguise.

It’s not enough to just point these devices out. The real analysis comes from explaining how they work to advance the author's argument. How does that "runaway train" metaphor stir up a sense of panic and make the audience crave drastic action?

These strategies aren't just literary flair; they're measurable tools of persuasion. A large-scale historical study found that persuasion attempts were successful about 56.1% of the time across 18 different rhetorical strategies. Researchers could even pinpoint which techniques were most effective. This shows that analyzing these devices is key to understanding how persuasion really works. You can read more about these fascinating historical rhetorical findings on nature.com.

When you expand your toolkit beyond ethos, pathos, and logos, your analysis becomes far more nuanced. You start to see not just what the author is arguing, but the intricate craftsmanship behind it. That's the mark of a truly great rhetorical analysis.

Building an Arguable Thesis and a Clear Outline

With all your notes and evidence in hand, you’re ready to build the engine of your essay: the thesis statement. This isn't just a summary; it's a sharp, arguable claim that drives your entire analysis. Honestly, your whole essay lives or dies by the strength of this one sentence.

A weak thesis just states the obvious. Think: "The author uses pathos to connect with the audience." Yawn. A strong thesis, on the other hand, makes an argument about how and why specific rhetorical choices work together to create a certain effect for a specific audience.

Crafting a Thesis That Makes a Claim

Your thesis should be the answer to one central question: "How does this author try to persuade this audience, and what’s the overall effect?" It needs to be specific enough that you can actually prove it in the space you have.

A great way to get started is with a simple formula. It’s not fancy, but it forces you to connect the dots between the author, their strategy, their audience, and the outcome.

Thesis Formula: In [Text Title], [Author's Name] uses [Rhetorical Strategy 1], [Strategy 2], and [Strategy 3] to [Intended Effect/Purpose] for [Specific Audience].

This isn't your final product, but it's a rock-solid starting point. Let's imagine we're analyzing MLK's "I Have a Dream" speech. A first pass at a thesis might look like this:

Initial Draft: "In his 'I Have a Dream' speech, Martin Luther King Jr. uses emotional anecdotes, biblical allusions, and repetition to inspire hope in a nation divided by segregation."

This works because it’s arguable. Someone could counter that his strategies were meant to provoke anger, not just inspire hope. If you’re feeling stuck, our complete guide on how to write a thesis statement has more detailed examples and structures to help you get your argument on paper.

Choosing Your Organizational Structure

Once you have a working thesis, you need a blueprint for your essay. Your outline is that blueprint. It ensures your argument flows logically from one point to the next, instead of jumping all over the place.

For a rhetorical analysis, you have two fantastic options for structuring your body paragraphs. The best choice really depends on the text you’re analyzing. There’s no single "right" way, so just pick the one that makes your case most effectively.

Option 1: Organize by Rhetorical Strategy

This is the most common approach, and for good reason—it’s super clear. Each body paragraph zeroes in on a single rhetorical strategy or appeal.

- Paragraph 1: Focus on the author's use of emotional language (pathos).

- Paragraph 2: Analyze how they build credibility (ethos).

- Paragraph 3: Discuss their use of specific statistics (logos).

This structure is perfect when the author uses distinct, powerful strategies that you can analyze on their own. It keeps your essay laser-focused and makes it easy for the reader to follow along.

Option 2: Organize Chronologically

Sometimes, the power of a text builds over time. The author takes the reader on a journey. When that's the case, organizing your analysis chronologically just makes more sense. You follow the text from beginning to end, analyzing the rhetorical choices as they pop up.

This method works beautifully for speeches or articles that have a clear, step-by-step progression. You might analyze how the author first establishes a problem, then ramps up the emotional stakes, and finally presents a logical solution.

Writing Topic Sentences That Guide Your Reader

No matter which structure you choose, every single body paragraph needs a strong topic sentence. Think of these as signposts for your reader.

A good topic sentence does two things: it introduces the paragraph's main point and clearly links that point back to your main thesis.

A weak topic sentence is just a label. "The author uses statistics." Okay, and?

A strong one makes a claim: "King strategically employs statistics about voter suppression not just to appeal to logic, but to create a sense of urgency and injustice among his listeners."

See the difference? The second example is so much more effective. It tells the reader exactly what the paragraph will prove and connects it directly to the bigger argument about creating urgency. By building a solid thesis, a logical outline, and clear topic sentences, you’re creating a powerful framework that turns your observations into a genuinely persuasive analysis.

Writing Body Paragraphs That Actually Analyze

This is where a good rhetorical analysis becomes a great one. It's easy to spot rhetorical strategies, but the real challenge is explaining how they work. So many writers fall into the trap of summarizing the text instead of analyzing it. Your body paragraphs are your chance to build a convincing case for your thesis, one piece of evidence at a time.

Think of each paragraph as a mini-argument supporting your main claim. It needs a clear point, solid proof from the text, and—most importantly—your explanation of how that proof persuades the reader.

The Claim-Evidence-Analysis Framework

Every body paragraph has three essential jobs. This simple structure keeps you locked on analysis and stops you from just repeating what the author said. It’s a reliable way to make sure every sentence serves your larger argument.

Here’s the breakdown:

- Claim: Kick things off with a strong topic sentence. This sentence should introduce the specific rhetorical choice you're digging into and make a point about its purpose or effect. For a deeper dive, check out our guide on creating powerful topic sentences for body paragraphs.

- Evidence: Back it up with a direct quote or a specific, detailed paraphrase from the text. This is the proof. Don’t just drop it in—weave it smoothly into your own sentence.

- Analysis: This is where the magic happens. Explain how the evidence proves your claim. Unpack the quote, discuss the word choices, and connect it all back to the audience's likely reaction and your overall thesis.

Key Takeaway: Your analysis should always be longer than your evidence. If you have a one-line quote followed by four lines of explanation, you're on the right track. If it's the other way around, you’re probably summarizing.

And if just getting words on the page feels like a struggle, remember that happens to everyone. Learning how to overcome writer's block can give you the push you need to get moving.

From Summary to Sharp Analysis

Let's see this framework in action. Imagine you're analyzing a speech where a politician is arguing for new environmental laws.

A paragraph stuck in summary mode might look like this:

Summary (What to Avoid):

The senator uses a statistic to support her point. She says, "Over 70% of our state's rivers are now considered unsafe for swimming due to industrial runoff." This fact shows that the pollution problem is serious.

This paragraph identifies the evidence but the "analysis" just states the obvious. It tells us what the senator said, not how her choice persuades the audience.

Now, let's inject some real analysis:

Analysis (The Goal):

The senator strategically deploys a stark statistic to trigger a sense of alarm and urgency in her audience. By stating that "over 70% of our state's rivers are now considered unsafe," she transforms an abstract policy debate into a tangible threat to community well-being—affecting everything from summer recreation to public health. The word "unsafe" is a powerful emotional trigger, designed to make listeners feel that their families are in immediate danger, thereby making them more receptive to her proposed regulations.

See the difference? This version analyzes word choice ("unsafe"), explains the strategic purpose (creating alarm), and connects the evidence to a specific audience reaction. That's real rhetorical analysis.

Body Paragraph Revision Checklist

When you’re reviewing your draft, run each body paragraph through these questions to sharpen your analysis.

- Does my topic sentence make an arguable claim? It needs to state a point about the author’s strategy, not just identify a device.

- Is my evidence specific and well-integrated? Avoid long, blocky quotes. Weave shorter phrases into your sentences.

- Is my analysis longer than my evidence? This is the golden rule.

- Do I explain the "how" and "why"? How does this word choice create an effect? Why did the author choose this specific strategy for this audience?

- Does this paragraph connect back to my thesis? Every paragraph should be another brick in the wall of your main argument.

By consistently using this framework and checklist, you'll move past simple summary and start writing body paragraphs that offer deep, convincing insights into how a text really works.

Common Questions About Rhetorical Analysis

As you dig into this kind of essay, a few questions always seem to come up. It's totally normal to hit a couple of sticking points. Let's clear up some of the most common hurdles so you can tackle your rhetorical analysis with more confidence.

Getting these issues sorted out early can make the whole process feel a lot less intimidating.

Analysis vs. Summary: What’s the Difference?

This is the single biggest trap I see students fall into. It’s so easy to spend your entire essay just explaining what the author is saying. But a rhetorical analysis isn't a book report. Your real job is to explain how the author built their argument to persuade a specific audience.

Think of it this way:

- Summary answers, "What is the author saying?" It just recounts the main ideas.

- Analysis answers, "How is the author persuading the audience?" It digs into the strategic choices—word choice, structure, emotional appeals—and explains their intended effect on the reader.

The key takeaway: If your paragraphs are just restating the author's points, you’re summarizing. To analyze, you have to focus on the techniques the author uses and explain exactly how those techniques are supposed to make the reader think or feel.

How Do I Choose Which Strategies to Focus On?

A strong piece of writing is usually packed with rhetorical strategies, and you can't possibly cover them all. Trying to do that just leads to a shallow, list-like essay. The trick is to be selective.

Go back to your notes and look for patterns. Did the author lean heavily on emotional stories? Did they build their credibility in a particularly clever way?

Focus on the strategies that do the most work. Your thesis should be your guide here. Pick the 2-3 strategies that best support your argument about the text's overall persuasive power. Quality over quantity is always the right move.

Can I Analyze Something That Isn’t a Text?

Absolutely. The principles of rhetoric apply to any form of communication designed to persuade, not just articles or speeches. In fact, analyzing visual media can be a fantastic way to sharpen your skills.

You can apply the same core concepts to things like:

- Advertisements: Ads are masterpieces of persuasion. Look at the imagery, slogans, music, and emotional narratives they use to sell an idea.

- Political Cartoons: These use caricature, symbolism, and irony to make a sharp political point with very few words.

- Photographs: A single, powerful image can tell a story and trigger a strong emotional response (pathos). Think about the composition, lighting, and subject.

- Films: Movie scenes are loaded with rhetorical choices. The dialogue, music, and even the camera angles all work together to persuade you to feel a certain way about the characters and events.

When you're looking at a non-textual source, your job is the same. Identify the creator, the audience, the message, and the context. Then, break down how the specific visual or auditory choices work to achieve a persuasive goal.

Feeling ready to tackle your draft but worried it still sounds a bit robotic? Natural Write can help. Our free platform transforms AI-generated text into natural, human-like language that bypasses AI detectors with ease. Polish your tone, improve clarity, and ensure your final essay sounds like you. Humanize your work in one click at https://naturalwrite.com.